MILITARY DRONES: FUNCTIONALITY AND EVOLUTION EXPLORED

COMMENT

SHARE

As the Russia-Ukraine war heads into its 30th month, one type of weapon has emerged as the preferred choice for military commanders on both sides of the conflict – drones. In June 2025 alone, Russia launched an estimated 5,438 into Ukraine and, before the end of July, had employed almost 5,000 more. The numbers for Ukraine are harder to nail down during that same period, but still impressive. According to the Russian Defense Ministry, their forces downed 2,303 Ukrainian drones in the first three weeks of July – an average of 109 drones per day.

Why have drones become so popular during this conflict? It mostly boils down to money. As compared to modern surface-to-surface and air-to-surface missiles and bombs, drones are relatively cheap, easy to build, very accurate, expendable and difficult to defend against given their small size and sheer numbers.

Ultimately, the overriding reason is that they’re effective. At this point in the war, some reports estimate that up to 80% of all daily combat losses are the result of drone attacks.

In this article, we’ll take a look at the history of drones, how Russia and Ukraine are currently employing them, and what drone programs the US Department of Defense is pursuing. The success of drone operations in the Russia-Ukraine War has had a big impact on how modern militaries will invest in these technologies moving forward.

Military Drone Technology: An Overview

In this article, we’ll use a very specific, and somewhat simplified, definition of a drone.

A drone is an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) or unmanned aircraft system (UAS) with no human pilot, crew, or passengers on board, but rather is controlled remotely or is autonomous. Sometimes, they are called a Remotely Piloted Vehicles (RPV).

Evolution of Military Drones: A Historical Perspective

Drones are not new, although the technology associated with them has improved dramatically in recent years.

WWI & WWII

Britain and the USA developed and flew the first pilotless air vehicles during WWI. The Brits called their drone the Aerial Target. It was a small radio-controlled aircraft first tested in March 1917 while their Yank cousins built an aerial torpedo known as the Kettering Bug that first flew in October 1918.

The Kettering Bug looked much like a regular bi-plane of the day and could hit targets up to 75 miles away at speeds of 50 miles per hour. Both showed promise during flight testing, but neither were used in combat.

Between the two world wars, development and testing of unmanned aircraft continued. In the 1930s, the British produced several radio-controlled aircraft used as targets for training purposes. This is where the term “drone” began, inspired by the name of one of these models, the de Havilland DH82B Queen Bee. The US also manufactured radio-controlled drones used for target practice and training.

Vietnam War

During the Vietnam War, the USA first deployed reconnaissance UAVs on a large scale to scout enemy targets and positions. The USA also began to use drones in a range of new roles, such as acting as decoys in combat, launching missiles against fixed targets, and dropping leaflets for psychological operations.

The USAF also got into the habit of turning retired fighter aircraft into drones that they then used as aerial targets to train their fighter pilots employing real guns and missiles.

This practice began in the 1950s when the USAF turned the F-80 Shooting Star into a target drone and gave it the designation QF-80. Today, the DoD flies QF-16s as target drones and plans to fly the aircraft in this role until 2035.

Operation Enduring Freedom & Operation Iraqi Freedom

Since the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the United States, and several of its allies and enemies, has significantly increased its use of drones. During Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq, the MQ-1 Predator proved the value of UAVs to the counter-terrorism fight.

The Predator was the result of a cooperative DoD-CIA program that started in the 1980s. Initially employed purely as an intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) platform, providing real-time video surveillance information from its electro-optical camera, the Predator was soon upgraded with two Hellfire missiles turning it into a lethal killing machine.

The MQ-1 paved the way for the development and fielding of the MQ-9 Reaper. The Reaper is a larger, heavier, more capable aircraft than the Predator and can be controlled by the same ground stations.

The Reaper’s greater power allows it to carry 15 times more ordnance payload and cruise at about three times the speed of the MQ-1. In addition to the Hellfire missiles, the Reaper can also carry precision guided munitions more commonly carried by fighter aircraft.

The Use of Drone Technology Expands

The successes of the Predator and Reaper in the Global War on Terror led to a veritable explosion of drone technology – both large and small – in the military.

The Large Side

On the large side, the USAF fielded the RQ-4B Global Hawk in 2001, a high-altitude long endurance (HALE) platform covering the spectrum of intelligence collection capability to support forces in worldwide military operations.

The Navy flies a variant of this platform called the RQ-4C Triton. The aircraft are big – 47 feet long with a wingspan of 130 feet. That’s as big as some commuter jets and they can fly missions of up to 30 hours at high subsonic speeds.

The Small Side

On the small side, the DoD has developed and fielded a slew of small UAVs that largely perform reconnaissance missions for ground forces in close proximity to enemy forces. The most ubiquitous of these systems might be the RQ-11 Raven – a small hand-launched remote-controlled unmanned aerial vehicle.

The US Army introduced the Raven 1999 as the FQM-151, but in 2002 developed it into its current form. The UAV is launched by hand and powered by a pusher configuration electric motor. It can fly up to 10 km at altitudes of approximately 150 m above ground level or over 4,500m above mean sea level at speeds of 45–100 km/h.

Much like the first Predator, it’s used exclusively for ISR operations, but on a much smaller scale. The small UAVs used by Russia and Ukraine today have more in common with the Reaper. They have evolved into mini killing machines.

The Civilian Side

On the civilian side, drones now have many functions, ranging from monitoring climate change to carrying out search operations after natural disasters, photography, filming, and delivering goods.

Their uses seem to grow every day. Business is booming in the drone industry.

Russia-Ukraine Conflict: Military Drone Utilization

Drones have become a crucial element in the Russia-Ukraine War and have been extensively used by both sides for a variety of missions.

Ukraine has been particularly innovative in the development and employment of drones using them for a wide range of missions including surveillance, strike, logistics support and even prisoner capture.

Russia’s employment of drones has been less diverse but, perhaps, even more deadly. The Russian government has poured tremendous resources into drone production significantly scaling up its production capability particularly for drones that can strike deep into Ukrainian territory.

Ukrainian Drone Employment

Three of the more innovative ways Ukraine has employed drones during its war with Russia have been the establishment of a “Drone Wall Defense” along its eastern border, using drones to fly logistics support missions and using drones to strike targets much deeper into Russian territory than many analysts thought was possible when the war began.

As Russia’s summer offensive continues along hundreds of miles of land between the two combatants, Ukraine’s overstretched military has found itself heavily reliant on drones to prevent major breakthroughs.

The Ukrainian military’s innovative use of UAVs to create a layered defense between Russian forces and their own is referred to as a “drone wall.” If this drone wall can prove itself by blunting Putin’s big offensive, this will likely shape future defensive doctrine in military academies across the globe. In fact, many have suggested that Ukraine’s innovative use of drone technology has already had that impact.

Since the Russian invasion in 2022, Ukraine’s use of UAVs has evolved dramatically. Some have even referred to the Russia-Ukraine conflict as the world’s first full-scale drone war. As the invasion enters a fourth bloody summer, it’s been estimated that drones account for around 70 percent of all Russian and Ukrainian battlefield casualties.

Ukraine was forced to develop innovative drone tactics to counter the Russian numerical advantage out of sheer necessity. After Russia won the Battle of Avdiivka in early 2024, Ukraine faced severe shortages of artillery amid delays in anticipated US aid. The government responded by turning to drones as a cheap and effective substitute for more conventional munitions.

Conducting Surveillance & Airstrikes

While drones can’t completely replace the firepower of artillery, Ukraine has found that drones can create defensive corridors many miles deep and this has proven to be remarkably effective. Conducting both surveillance and airstrikes, drones have made it difficult for Russian forces to launch large-scale offensive operations. The numbers speak loudly. Britain’s International Institute for Strategic Studies estimates that Russian losses in 2024 included around 1400 tanks and more than 3700 armored vehicles due primarily to Ukrainian drone attacks.

Resupply Missions

On the non-kinetic side of operations, Ukraine has also increasingly used drones to resupply troops, particularly in areas where the threat of Russian attacks is high. Some units report that small resupply drones account for about half of their resupply missions. Ukraine even uses ground robots to support some of these missions. It has also modified agricultural drones to support deliveries to the front lines.

Ukraine has been very successful striking strategic targets deep within Russia, shocking those analysts who believed it would never be able to accomplish these strikes for both political and practical reasons. To accomplish this mission, Ukraine has used a wide variety of drones mostly sourced from foreign defense companies. However, it is rapidly enhancing its ability to produce all types of drones domestically.

The "Kamikaze Drone"

Ukraine uses these so-called long range “Kamikaze drones” for attacks on strategic targets deep inside Russia. These attacks serve several purposes. The targets themselves, such as oil storage sites and airfields, are of strategic importance. The attacks also strive to make the Russian population more aware of the war. In addition, it stretches Russian air defenses forcing them to deploy further away from the front lines.

While the long range drones have created headaches for Russian forces, the boldest and most innovative use of drones by Ukraine during the war involved the employment of shorter range drones against strategic targets on enemy air bases deep inside Russia. Here’s how that played out.

On June 1, 2025, Ukraine delivered a shocking blow to Russian strategic aviation with a closely coordinated drone offensive that targeted four Russian air bases. Ukraine pulled off this mission by concealing drones in semi-trailer trucks near the air bases and launching them via retractable roofs thereby enabling a rare element of surprise. By launching the drones from close proximity to their targets, they were able to bypass Russian defenses and ensure deep penetration into rear areas. This marked the first Ukrainian strike on a target within Siberia – a huge escalation in their ability to reach Russian targets.

The successful operation used 117 drones and destroyed 34 percent of Russia’s cruise missile-carrying aircraft, notably Tu-95 and Tu-22M3 bombers, as well as an A-50 airborne early warning and control aircraft, a $500 million dollar asset that will be almost impossible for Russia to quickly replace due to construction constraints.

Russia employs the bomber aircraft to launch cruise missiles against Ukraine. The Ukrainian attack marked a massive setback to Russia’s Air Force. Russia has not been quiet.

Russian Drone Employment

In comparison with their Ukrainian adversary, Russia’s employment of drones during the war has been far less diverse.

The Shahed 136

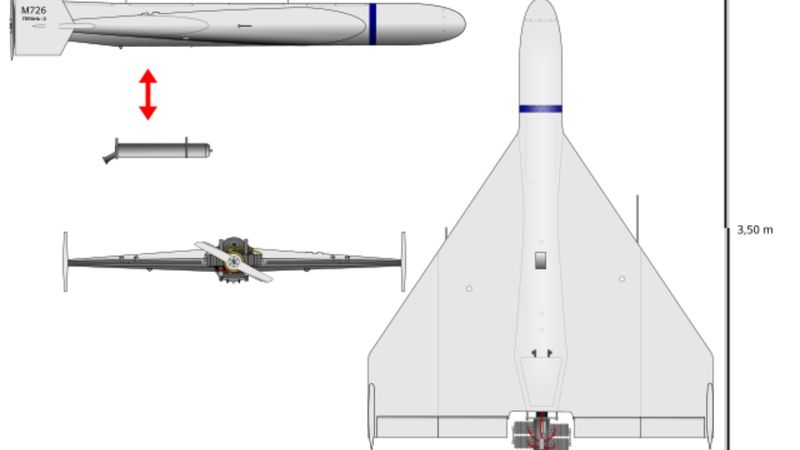

Russia’s focus has been on the employment of the Shahed 136, an Iranian designed and built UAV that is capable of striking targets deep in Ukrainian territory from its launch points in Russia.

The Shahed, called the Geran-2 by Russia, has become the preemptive weapon of choice during air attacks on Ukraine normally being launched in waves alongside larger and more powerful ballistic missiles. This has proven to be an effective tactic for the Russians as the large scale attacks have made it more difficult for Ukrainian air defense systems to successfully intercept the overwhelming number of targets.

During the evening of July 8 and into the next morning, Russia launched 728 drones and 13 missiles at targets across Ukraine. While Ukraine contended that most of the targets were intercepted or jammed, the resulting damage was significant. Russia will seek to increase these types of massive attacks.

After Iran indicated that it was feeling less politically comfortable supplying Shahed missiles to Russia, a former agricultural company called Albatross moved forth with domestic production of the UAV. In July 2023, Russia opened the Yelabuga Drone Factory in the Republic of Tartarstan, about 1,300 kilometers from the Russia-Ukraine border.

After achieving initial production rates of about 130 drones per month, the factory aims to produce up to 310 drones per month during the summer of 2025 at a cost of about $80 thousand per unit. Given the recent success of large scale drone-heavy air attacks against Ukraine, Russia hopes to achieve a one-night assault of up to 2,000 drones by the end of the summer. They won’t get there without Albatross hitting its production numbers.

U.S. Military Drone Strategy: Future Developments

The success of drone warfare on both sides of the Russia-Ukraine conflict has influenced decisions made by the US Army, as well as other nations, on their future drone procurement and fielding strategy. However, the US Air Force has been less influenced, instead placing more emphasis on advanced drone technology designed to deliver UAVs that can operate as autonomous wingmen to manned fighter aircraft.

The US Army plans to acquire a family of small uncrewed aircraft systems (sUAS) for ground maneuver elements at the battalion level and below to provide real-time reconnaissance, surveillance, and target acquisition (RSTA) capabilities. This role is today largely filled by the RQ-11 Raven.

Plans for the Next Generation

Army

The Army plans to phase the RQ-11 Raven out of service as part of a broader “rebalance” of the Army’s aviation investments.” One of the key differences between the currently-fielded UAS and the planned new systems is their configuration.

The Raven and Puma feature a conventional fixed-wing configuration, which potentially hampers their usefulness in restrictive terrain, such as urban or forested areas while the Army will prioritize a vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) capability in the form of either multirotor or hybrid-VTOL configurations for the new systems.

The Ukrainian military uses this VTOL configuration on almost all of its battlefield drones. Another big difference has to do with weapons carriage.

In contrast to the Raven and Puma, which were designed largely to conduct surveillance and reconnaissance, the Army may require the next generation of small UAS to conduct a greater variety of missions, including launching lethal strikes and relaying communications for other drones and ground units – two more lessons it learned from the war in Ukraine.

USAF

The USAF has placed its drone focus elsewhere. In March 2025, the USAF officially designated two of its newest developmental UAVs, aircraft that promise to be so advanced it would almost be an insult to call them UAVs.

The Air Force designated two Mission Design Series within its Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) program – the General Atomics YFQ-42A (General Atomics) and the Anduril YFQ-44A.

These two aircraft represent the first in a new generation of uncrewed fighter aircraft and, according to the USAF, both will be crucial in securing air superiority for the Joint Force in future conflicts. These aircraft are designed to leverage autonomous capabilities and crewed-uncrewed teaming to defeat enemy threats in contested environments.

The USAF’s vision is for these CCAs to “team” with manned fighter aircraft like the F-35 and the recently announced F-47 as dedicated wingmen, effectively wingmen without a pilot. As development proceeds, the growing sophistication of Artificial Intelligence (AI) capabilities will drive the level of autonomy that these new platforms will enjoy.

In theory at least, the CCAs will be able to take initial instructions from their human flight lead and be able to execute their planned mission with minimal human input as the mission is executed. This would be true for the full range of missions flown by USAF fighter aircraft whether they’re shooting down enemy fighters or dropping precision weapons on targets located in heavily defended territory.

The two CCAs are expected to begin flying this summer and the USAF aims to reach a full scale production decision in Fiscal Year 2026. That’s quite an ambitious schedule for such an advanced capability.

In addition to the CCA aircraft, the USAF is also investigating the development and procurement of other UAV systems that perform the ISR role. Just as the aforementioned Global Hawk Block 40 effectively replaced the manned E-8C Joint Surveillance target Attack Radar System (JSTARS) more than two years ago, the service sees both UAVs and, more importantly, space-based systems as the natural successors to aircraft like the E-3 AWACS and other ISR platforms.

The Next Drone Challenge

As both Ukraine and Russia pump up its ability to produce more drones that can strike targets, a new challenge has emerged. How do you defend yourself against these drones?

While currently fielded air defense systems, like the Army’s Patriot, can be very effective against drones, waves of hundreds of these relatively inexpensive aircraft can overwhelm air defense strategies. In addition, a $1 million Patriot missile is an awfully expensive piece of hardware to use against an $80 thousand drone like a Shahed. The Ukrainians and their European Union benefactors think the solution may be found in relatively cheap defensive drones that intercept and destroy enemy drones.

Ukraine will receive 33,000 AI-powered drone kits under a $45 million contract funded by the US DoD in a move that aims to create a defensive shield of smart drones to defend against Russian attacks.

These devices can transform regular drones into autonomous hunters capable of tracking targets up to one kilometer away. Earlier versions of the software have been employed by Ukrainian forces since Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022. Upgraded versions of the software adds enhanced ability for intercepting thousands of the Shahed drones used by Russia.

The key element of both Russia and Ukraine’s drone employment strategy will be the ability of both nations to simply produce more drones as quickly as possible. While Russia hopes to build up to 310 Shaheds per month at its new Tatarstan factory, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy recently announced that domestic production of interceptor drones is underway, with a goal of manufacturing at least 1,000 units per day.

The drone war is far from over and further innovation is sure to follow.

Related reads:

Join the Conversation

BY GEORGE RIEBLING

National Security Analyst at VeteranLife

Air Force Veteran

George Riebling is a retired USAF Colonel with 26 years of distinguished service as an Air Battle Manager, including operational assignments across five command and control weapon systems. He holds a Bachelor of Journalism, Radio & Television from the University of Missouri. Following his military c...

Credentials

Expertise

George Riebling is a retired USAF Colonel with 26 years of distinguished service as an Air Battle Manager, including operational assignments across five command and control weapon systems. He holds a Bachelor of Journalism, Radio & Television from the University of Missouri. Following his military c...