RETURN TO BASE PODCAST EP. #1: BESSEL VAN DER KOLK: KEEPING THE SCORE

COMMENT

SHARE

[buzzsprout episode='9241278' player='true'] Listen on Apple PodcastsListen on SpotifyListen on Google PodcastsListen on Amazon Music

Introduction

In this, the inaugural episode of Return to Base podcast, we welcome Dr. Bessel van der Kolk M.D.. Van der Kolk is a psychiatrist that has been conducting research in the field of Traumatic Stress Studies for decades. He’s also the best selling author of The Body Keeps the Score. In Return to Bases’ first ever podcast with Bessel van der Kolk, we discuss the nature of trauma, how trauma rewires the brain as a defense mechanism, and touch on various treatment options. We also discuss the recent collapse of the 20 year mission in Afghanistan.

Return to Base Podcast Ep. #1: Bessel van der Kolk: Keeping the Score

Cliff: [00:00:00] Hello. We're with Dr. Bessel van der Kolk MD. He spent his career studying how children and adults adapt to traumatic experiences. He has translated his findings from neuroscience and attachment research to develop and study a range of treatments for traumatic stress in children and adults. He's the author of the best-selling The Body Keeps the Score, which is helping transform our understanding of trauma and explores innovative ways to confront trauma. Dr. van der Kolk's patients come from all walks of life and [00:01:00] experiences, but for the purpose of this conversation, we're going to focus on veterans and issues involving post-traumatic stress disorder. Dr. van der Kolk, welcome to the program. Dr. van der Kolk: Thank you. Good to be here. Cliff: Great. Well for those listeners who haven't read your book or aren't familiar with your work, and I hope I get this right, The Body Keeps the Score explains that the brain, as a self-defense mechanism, tries to hide our traumatic experiences from us and our bodies, yet our bodies don't forget. And this battle between our mind and the body can have grave consequences to our health. Would you mind elaborating on that? And I hope I got that right. Dr. van der Kolk: That's not quite how I would have said it. You know, we're complex creatures, all of us human beings. It's really good to hang out with little babies and little babies cannot talk yet. They don't understand anything about the world, but they do all kinds of things. They eat and they sleep and they fart and they suck and breathe. No babies already do a [00:02:00] lot of things and they get scared and they get angry and they have a lot of emotions; that's because they have a small part of their brain that’s evolved in self-preservation is already aligned. That's also the part of the brain where trauma hits. So trauma hits a lot in neuroscience, we call the housekeeping of the body. And that's when you get traumatized, your body doesn’t work for you anymore. You have feelings, emotions, sensations that are disturbing and your mind is trying to - just like you see little kids, when they start talking, they start going to school - they create a new reality. Now, this sort of social reality. So we live in ideologies and systems. Uh, concepts the world that very much depends on where we live and who we hang out with. But the core part that takes care of ourselves and our [00:03:00] bodies is sort of almost like a separate part. So something terrible happens to you, and you get raped or you see your best friend get killed and you are heartbroken. You feel terrible. And then you say to yourself, okay, man up, let’s be strong. Let's go do it. Everybody says, okay, it's over. You say, okay, it's over. And then you start behaving as if you're over it. And you keep sort of pretending like it didn't matter. And before too long, you're able to talk yourself into that it doesn't matter, but the primitive part of your brain doesn't have the capacity to rationalize it and continues to experience all kinds of stuff as if your life is in danger, as if people tried to hurt you. And you get this internal war to your rational brain and your emotional brain, and the result of that war is that you feel out of touch with yourself and out of tune with yourself. [00:04:00] Things keep happening to you. You keep doing things that other people are, makes other people angry or makes other people scared of you. And then when you end up, you see you become deeply ashamed about who you are. There’s a deep deep feeling of shame, of there's something wrong with me. And I need to be careful that nobody finds out there's something wrong with me. And so you start ranging your life around, uh, trying to pretend like everything is just fine, but it isn’t. And then oftentimes very many people at that point start drinking in order to sort of tranquilize themselves against these sensations or they start taking drugs. What's astounding to me, for example, isn't the whole opioid epidemic. Everybody says it's about opioids. No, it's about people who take opioids. Yeah. Most people I know if I say, "Hey, have a little heroin," would say, [00:05:00] "Like hell I don't take, go take heroin." But if you feel terrible and you feel like the world is out to get you, uh, heroin might give you a nice little piece of relief. So you start taking heroin. How so? It's just, people start taking these drugs in order to deal with feelings and sensations that they can't understand. Cliff: Interesting. So with all that understood, should we suspect that the goal of treatment in the end should be to forget the trauma, to remember it, to remember in a different way? Dr. van der Kolk: To know this happens and to know what happens, but to know when it happens. That's the goal of treatment - is to go, "Yes, when I was 18 years old, I was in a war zone, and I saw my best friend blow up. And then I became so angry that I mowed some kids down.” Terrible, terrible thing. Both your friends getting killed and work you may have done. And the response to it [00:06:00] was horrendous. You don't want to remember that; you don't want to remember how heartbroken you were, how irate you are. So you go to push it away. And in fact, you need to go back and say, "Yes, this is what happened. It happened to me when I was a stupid 18-year-old kid who didn't have the resources to deal with it any other way." Really it's really feeling what you, as a creature, have gone through and say, "Yeah, this is what I went through. But it happened back then." You really know the difference between what you're feeling today and what you're feeling back there. Cliff: Interesting. You know, a lot of times I think to myself when we discuss the past and how people dwell on it, I remind them, and I'm not a super religious person, but I remind them of the serenity prayer, which says, you know, we must accept the things we cannot change. And, and that kind of reminds me of [00:07:00] something like that, where it's important to acknowledge that these things that happen rather than pretending that they didn't and knowing that we can't change the past. Dr. van der Kolk: And there's another complex story here. And as the trauma changes your brain, let me give you an example. I've seen, I know quite a number of people, one of whom is actually a good friend of mine, who are foreign correspondents, and they go to Afghanistan and Eritrea and the Congo and Libya and Syria, and you see all these horrendous things. And they are tense, and they are uptight. But when they come to Cambridge, Massachusetts, they go to a panic reaction because their brain has changed to be alive in extreme danger, but they feel terrified when they feel safe. And so I think a lot of people who [00:08:00] have been exposed to low trauma feel better when there is a high level of anxiety, high level of danger around them. And oftentimes they create a feeling of danger because their brain is good at dealing with danger. Their brain is terrible at dealing with putting diapers on a 1-year-old. Cliff: Right. Yeah. Well, that can be frightening for anybody. I know I have two boys, so it's kind of like a war zone anyways. Dr. van der Kolk: The difference, you know, and when you're a combat vet, you may see it as a war zone. In fact, they're just little babies who need to have their diapers changed. The big, evoke all these feelings like, "Oh my God, this kid's not listening to me." These intense reactions to minor issues. Okay. Cliff: Interesting. So, sir, one of your first jobs out of school was as [00:09:00] a staff psychiatrist at the VA clinic in Boston. Dr. van der Kolk: After I finished the 29th grade. Yeah. Cliff: Hahaha. You know, I saw that you had, you had started your learning there really on how veterans react and the reactions from the Vietnam War. Dr. van der Kolk: My first job was to run a state mental hospital, the last state in the hospital before we sent the patients home. And that's also very interesting. But my next job was at the VA, yeah. Cliff: Okay, yeah. So your, your experience with the, uh, with the Vietnam war and the veterans, um, who came back from Vietnam, um, to help get the audience oriented, can you tell us a little bit more about your time there and, and how it's affected your career since you left? Dr. van der Kolk: Well, um, yeah, [00:10:00] veterans immediately just caught my attention and my interests and my fascination and my sympathy in part, I think, because I was born at the very end of the second World War, and as a small kid, uh, relatives came back from concentration camps. They came back from war zones. And so my early imprint of seeing a lot of people come back from the war and being intrigued with both their stories, but also how they would blow up from time to time or become very irascible or withdraw. Even as a kid, I was very fascinated by that. And then I started to work at the VA and here it is, you know, young guys, still, uh, powerful guys, uh, smart people and something has happened to them. They were frozen in their bodies. They kept exploding. [00:11:00] The waiting room at the VA was filled with, uh, the walls were filled with holes in the wall that people have put their fist through the wall. And then minor things they would blow up and become very angry. And I thought something happened to these guys, and these guys were able to fly a helicopter and rescue a platoon out of a war zone. You have to be very calm and very focused for that. And now when they sit in the waiting room at the VA and somebody says, you have to wait for five minutes, they get enraged. I feel like something happens. And so I got really intrigued with what might've happened to these guys that they had - that damaged them. And the next thing was that the VA was filled with people and we put people on the waiting list. And I said to my boss, "Is it okay if in the waiting room, even before people become patients, I meet with people and they can meet with each other because these [00:12:00] guys are hurting and they need to get some sort of support." And so we started these groups sort of, not as part of the VA, but outside of it almost. And, uh, we started off. I say, “We can talk about anything.” And somebody would say, "I don't want to talk about the war," and I said, "Fine. You can talk about anything.” Other guys said, "I don't want to talk about the war." And then, nobody's said anything for half an hour. And then you started to talk about the war. I mean, he talked about the war, they came to life and it turned out that the war had for them been by and large, a very powerful experience. They felt powerful. They felt skilled. They had felt great about their comrades, their friends, and then something had happened that sort of blew up that feeling they had of, "Boy, I'm a much better person than I thought I was. I can fire a machine gun. I can fly a helicopter. I could [00:13:00] repair complex engines.” And so they got a very good feeling from being in the military. And then something happened that broke them. And they go like, "Oh my God. And then offered up, they had dumb things that they felt very bad about. This later on came to be called a moral injury. But the moral injury piece was a very important part for most people that they had been involved in stuff that a conscience could not live with actually. Once they started to talk about it, they opened up. And the next thing that happens, interesting to me also, is that they took me in, but they could not take me in as a guy who had not been to Vietnam. So they gave me a uniform; they made me an honorary Marine. And so they had this need - that you belong to the in-group or you belong to the out-group. And, and if you want us to trust you, you have to become a Marine in my mind, [00:14:00] also. And so what I saw was this very strong bond, uh, based on the common experience people would, induct me into it. You know, in order to become acceptable. And what struck me at a time also is that these guys were extraordinarily loyal to people who had gone through similar experiences as they had gone through, but at a very hard time, connecting with people who had not had that experience. And so what struck me, for example, is that I met several of their wives who were very competent, smart people, but they had a hard time making a connection with their wives because their emotions were stuck in the war, and the wives were not part of the war experience. That's something I've not heard people talk about after Iraq and Afghanistan, but I bet that's still happening today. [00:15:00] Cliff: Right. It's an interesting thing you said there is how you grew up in, you know, right at the end of, of World War II. For our listeners, can you tell us where you grew up, and I'd like to know if, if you recognize the signs of trauma, looking back when you were a kid, and if it was just on the soldiers, the people who fought in the war, or as you know, civilians were very much a part of combat in World War II. How did you see that they were reacting to this trauma as you were growing up? Dr. van der Kolk: Well, you know, I was a kid, so you don't see the larger context. And basically I grew up very much like, you know, basically, you know, I grew up in a place very similar to what Kabul is like today. You know, people getting killed, people getting carted off, people evacuating like chaos. And I [00:16:00] don't remember that, actually. I was too young to remember it, but the imprints are there, and so what I saw after that is slowly a society that's starting to get back together, but I saw people do these weird things from time to time. Both people had been affected by the war, but also people in civilian life, of course. So I'd never, in my mind, even to this day have made a very clear distinction between civilian trauma and war trauma. In many ways, it's the same thing. Girl, a girl who gets gang raped in high school has a similar fundamental experience as a guy who goes off to war and sees atrocities. The core experience is one of, “Oh my God. This is too much for anybody to bear.” Yeah. Cliff: Okay. So, in your experience, you brought up Kabul, you brought up the War on Terror veterans. Have you [00:17:00] seen, are there some similarities or differences that you've seen from the folks who came back from Vietnam to the people who served in the Gulf war? The first Gulf War to post-9/11 veterans and their trauma. I know it’s different for everyone but - Dr. van der Kolk: I'd be very intrigued by this question. I don't know the answer to that because I've not seen enough people who were in Iraq and Afghanistan to be able to generalize that I saw a large number of people who came back from Vietnam, who were my age at the time. And what struck me at that time is that - I grew up - my parents were second World War veteran people, and the second World War veterans were different from the Vietnam veterans, and I studied it scientifically and second World War veterans put things into their bodies, and they, by and large, mainly became medically ill. They had heart problems, bowel problems, [00:18:00] muscle problems, but didn't, did not talk about the psychological problems. Then, Vietnam comes along and things are mainly acted out in terms of people's relationships with their families and people’s relationships with their work. Historically, the culture you live in determines to some degree how you deal with, how you organize your traumatic experiences. So my hunch is that today people will look somewhat differently than they did after Vietnam, but I've personally not had that capacity and not studied enough people to notice. For sure. Maybe you have thoughts about that. Cliff: I do have some thoughts, but I'm obviously not as informed or educated as you are. Dr. van der Kolk: But you know a lot of people. Do you have any, any thoughts about it? Do you think there is a difference yourself? Cliff: I think that there has to be something to [00:19:00] the way the Vietnam War veterans were received back home where they had to suffer in silence. A lot of times they weren't proud of their service. Dr. van der Kolk: See having lived through that, I don't completely buy that. There was a lot of common, what people commonly say, is the Vietnam veterans were treated with contempt and badly. That is very much not my experience. Yeah. And I lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and in, uh, Chicago and Hawaii during those times, uh, we were always very respectful to the people who had gone to Vietnam. And I don't, I don't think that's universally, too, that people received that badly. I think there's a sort of a myth that was created afterwards. Cliff: It's a painting that we're viewing now from a different perspective. Right? Dr. van der Kolk: You have all these mythologies that occur around this stuff, right. And everybody who's [00:20:00] traumatized feels cut off from their environment. As to when you come back from Vietnam, you may feel terrible about other people smoking dope and having a great time being home. And there may be a feeling of, oh, they, they despise us, but that's not my, that was not my personal experience. Cliff: That's refreshing, you know, honestly growing up and in the eighties and the nineties, the perception that, that I always understood was that there was a lot of contempt. Of course, that's just what you kind of see on TVs and movies. Dr. van der Kolk: And that’s, uh, the story that people started living by, yeah. Cliff: Well, when you ask, "How, how do I feel the global war on terror veterans are coping?" Obviously, we're not coping successfully in many ways. I think we have an enormous number of servicemembers who deployed to those regions. I, myself, am one of them. I have no personal [00:21:00] trauma that I can recall. Certainly I've been in places where other people would have been traumatized. For some reason, I haven't been. We'll, we'll kind of get to that a little bit, a little bit later. You mentioned actually something I also thought was interesting is that different cultures maybe deal with things in different ways. Do you think that your methods or your hypothesis for, for treatment and for diagnosis, does it work in the Eastern part of the world? For instance, does this work as a Western model? And can it work for, let's say our allies in Afghanistan who are dealing with something. Dr. van der Kolk: Our brains are basically the same from culture to culture, but our symbols are very different from culture to culture. And so, but I'd be very lucky that I've traveled a lot and with some depth. So I had a good immersion in India. I was [00:22:00] advisor to the commission of South Africa. So I was very, very close to what happened back then in Africa. Uh, traveled in South America, China, quite a lot, Japan. And I've actually - a lot of what I've learned, I've learned from other cultures. Western culture, as they're very much exemplified by the VA, is invested in two things. I call Western culture a post-alcoholic culture. Now, if you come from Europe, Europe, where you feel bad, you take a swig. The army, if you feel bad, you go to the commissary and you take a spirit. Like I don't know how it is today, but traditionally, the Army's a very alcoholic culture. And this is how you deal with your emotions, is by drinking. And the other thing you do, especially with people, you talk a lot, you explain a lot. So that's the two pillars of Western approaches to suffering. Uh, very much like that provided by the VA, but the VA you [00:23:00] get pills. Pills that incidentally, don't work. You know, I did the studies on these pills. Like, my name is on those papers. It didn't work. And yet people keep getting pills at the VA too! Huge amount of them. But they don't work. That's part of how I got involved in this whole PTSD research. Those pills didn't work, uh, and you talk or you reframe your cognitions. Then they go to Japan. I see people do Kendo fighting and I see them do jujitsu and I see them do Taiko drumming, and I call it. They do that to get their bodies back in shape and in tune. And they go to Africa and they follow Bishop Tutu, dealing with trauma. And what does Tutu do? He sings with people, and he dances with people, and he moves with people, and they write songs about their suffering. I go like, wow, we wouldn't do that in [00:24:00] the veterans administration, but clearly what he was doing in Africa, it was extremely powerful. And you go to China, I went to China early on when China was a really very tough society just after Mao died. And nobody talks about his habits. And in every place in China, people are doing Tai Chi. And I joined these Tai Chi people in China, doing Tai Chi, and I go like, wow, they don't do this because it's cute for the tourists. They do this because their relatives all got killed by Mao and they make these movements in order to help their bodies to become calm. So a lot of what I learned, I learned by stepping outside of the premises of Western culture of drugs and yacking. And of course what I always love is that the military has always known that. It was invented way back in Roman times, resurrected by some [00:25:00] Dutch prince, is that basic training - it's not about talking, not about understanding. It's not about taking drugs. It's about moving, singing, working, and having your body move. And after 12 weeks of basic training, you are a different person. A very different person. Cliff: Right, you’re part of a - part of a unit. Dr. van der Kolk: But I think what's so intriguing to me is that the military knows extremely well how to change a pimply, horny, difficult-to-get-along-with adolescent into a very good working person, huh? They’re very good at it. And it doesn't involve any of the methods that the VA uses to de-traumatize people. Cliff: Yeah, thank you, Uncle Sam for teaching me how to march and making me a man is what I say. Dr. van der Kolk: But you got something that has a very profound effect on people. Cliff: All those things you mentioned - in your book, you mentioned even [00:26:00] yoga - all those things are practices that people generally do together. And they have a sense of community, and it's almost like they're moving in unison as if in one body. So, very interesting. Dr. van der Kolk: Yeah. That's a huge issue. Synchrony is what makes the military possible. And feeling it, you're in touch with people in tune with people that are on the same wavelength makes for a powerful fighting force and a fighter unit. I bet the special operations guy, you notice very well, about how the movement and the reserves you and your, uh, your colleagues, are critical for the success of an operation. And it's that synchronicity with other people that disappears after you, after you leave the military, and you feel out of sync with everybody else who aren't you. An important question for all of us to ask is how we can help people whose body was held to be in sync in a different situation [00:27:00] to be in sync now that the war is over for you. So some of the best programs I know of for veterans, for example, is a program run by my friends. Stefan Wolford is DE-CRUIT. Uh, they do Shakespeare and acting with soldiers, with veterans, and they learn how to do a play together. Uh, in part, written on their own life experiences. Another program I know is called songwriting with soldiers, where they sing together and they move together. And so these are some of the dimensions that are not mainstream, but that are very powerful ways of helping you to get back in sync with other human beings Cliff: Right. Yeah. That's a powerful statement though. At the end of your career, you do largely fall out of sync with others. You don't, you don't go to formations, you're onto your own appointments. And a lot of people that is when they slip into, as you alluded to, alcoholism and other [00:28:00] self-destructive behaviors. You mentioned, you know, that our war is over. Pretty appropriate. 9/11? 20 years ago. I was in Germany. I was a young specialist at the time, but now we have the end of the war in Afghanistan. And it's been reported that the suicide hotline for veterans has had a significant increase in calls since the fall of Kabul. Why do you think that is? And do you think it's about what's been happening in Afghanistan that has triggered trauma that maybe some people haven't even recognized? Now, I venture to say that some of the trauma that people are experiencing right now has not manifested until now. Do you agree with that testament or that thought? Dr. van der Kolk: It’s a huge issue and that’s, you know, we are meaning making creatures. And so if you're, this happened at the end of the second World War or the second World War, it was a good war and we won the war. Actually, you won the war and liberated [00:29:00] me as a little baby, but there was no question who the victor of the war was. So soldiers would come home. They have their nightmares. They have their flashbacks. They have their troubles, but they say, “It was worth it. The sacrifices that I made in order to make the world safe for democracy.” And that is a very big consolation and you give up your heart and your soul for that enterprise. If you go to Vietnam, you realize that it was all in vain. Why the hell did you suffer so much? Why did your best friend get killed? Why did you do all these horrendous things? It was good for nothing. Afghanistan. You know, a lot of people know for a long time, this is not going to work out well. Most people, for a long time, have said, it's not going to work. Alexander the Great was defeated in Afghanistan and every other invader since that time. Who the hell do you [00:30:00] think we are, we're not going to do that. It's hubris, but still young kids get indoctrinated. You're doing this for a great cause and you do it. You do it because you want to believe in the cause. And then it all falls apart, and you go like, what the hell did I waste my time, my life on. It's a very big moral issue, you know, and then people find excuses, people to blame or people would be angry at, or somehow you need to come to terms that an enormous amount of your life is devoted to something that at the end failed and that’s a terrible thing to have to confront. Cliff: It is, it is. I know a lot of people out there are suffering. I've had those conversations in the last couple of weeks. But you're right. It's, it's a matter of why. A lot of questions unanswered. And you said moral. I'm [00:31:00] sorry, what was-? Moral injury. Is moral injury different than traumatic injury and or an injury that occurs as a result of a traumatic event? Dr. van der Kolk: So it goes very closely together. We are fundamentally moral human beings. You were trained as I think most military people are. If your friend gets shot, you stay behind and you'll do anything to get them out. That is fundamental morality. We are there for each other. You protect each other, et cetera, et cetera. And then in the war, things, you do things and things happen to you that in some ways really violate those core principles and living with that, uh, can become a great, great burden on you, particularly if you cannot say, but I liberated a concentration camp and hundreds of people lived because I did it. But if you say it's as good, and didn't resolve anything, [00:32:00] you live with a deep sense of, “What the hell am I doing with my life?” These are real challenges you know. I think nobody should minimize this. These are big issues. Yeah. Cliff: Alright. Changing gears just a little bit. And going back to trauma, do you believe all trauma is created equally? You kind of alluded to this earlier in your book. You speak at great lengths about the trauma associated with child abuse or child sexual abuse. Is there a difference in patients that suffered from child abuse or child sexual abuse? And let's say there's Veterans who suffered their trauma in war. Is their trauma any different than the child who this stuff happened to him at no fault of their own. Dr. van der Kolk: There is a difference, but the difference is not as black and white as we like to think it is because many veterans have [00:33:00] childhood trauma histories. About 70%, 80% of people who join the military have serious childhood problems. Often those people join the military because it's a great way to get out of poverty and out of alcoholic family stuff like that. So it's not just a war. We are an accumulation of experiences. Now there's a difference between today, my witnessing some horrendous event and when you're a little kid. And that's when you're a little kid, your brain grows according to the experiences that you have, and that's who you become. So when you're regularly being beaten up or you see family violence, you, that becomes part of you; that is who I am. I'm a child who is likely to get beaten or I'm a child who's only good for being sexually molested, or I will never have anybody touch me [00:34:00] anymore because, uh, that's too scary for me. I say, as a child, you get formed who you are, as by your trauma, and that determines, more or less, your identity. When you have had a pretty good childhood and then you join the military, terrible things happen to you. It is more or less how PTSD is defined as you're a relatively healthy person. And then something terrible happens to you and that changes things. But that issue is biologically fairly easy to treat. So if you're a well put together person and you see something horrendous, you can get very bad PTSD, but that sort of PTSD is quite responsive to the treatments that I talk about in my book. And a few of the treatments that VA does, but the VA does very few of them. Cliff: Interesting. So you say you had, I'm glad you brought this up. Cause that was actually going to be my next question.[00:35:00] Does being the victim of child abuse, child sexual abuse, something horrible in your growing up, does that then make you more likely to suffer from debilitating PTSD, if you go off to combat. So apples to apples, if I grew up in a nice nurtured home, but my buddy grew up in a home and he was terribly abused, we suffered the same trauma in a war zone. Does his post-traumatic stress outweigh mine somehow? Dr. van der Kolk: I think, you know, these diagnoses, I call them so-called diagnoses because they're not really scientific constructs—they're a list of symptoms. Right. If something horrendous happens to you both of you, you are likely to initially have the same symptoms of being very depressed. Uh, having flashbacks, having nightmares, uh, become [00:36:00] very irascible. But you, if you come from a very secure household, you're much more likely to respond to treatments than your buddy who was abused as a child. And it will be only the PTSD symptoms, but it will be harder to focus and to pay attention. It'll be harder to concentrate on the job, and it will be harder to have an intimate relationship with somebody because that earlier stuff starts affecting much more of your life. So it becomes a much more pervasive issue. Cliff: Right. So in summary, the person who has existing trauma. They address the trauma that happened in war, but they still may feel like a worthless person at the end of that treatment. Dr. van der Kolk: Feel worthless or also have a very hard time putting their teeth into something. Uh, being able to devote yourself to a job for example, [00:37:00] there was an interesting study, um, you'll never really hear quoted. There was a study of the guys who went to Harvard, who were in the second World War and it turned out that, so these guys came from privileged families. They had an extremely good education. They came back and they had, many of them had tremendous PTSD, but they did much better professionally than the average population. So they became accountants or lawyers or doctors. And were very good in focusing on what they had learned before their trauma and becoming very good at it. No, they couldn't have good relationships with people, their kids often then hated them, but they were very good in their work and they were much better at their work than their classmates who had not gone off to war. So the trauma made them hyper-focused and you met some people in your [00:38:00] unit who after they came back, became very good at something. Uh, they become very focused on becoming a very good businessman or race car driver or something. And as long as they can focus on one thing, uh, they can sort of ignore the rest of their lives. But so, but, what looks like he said, in addition to that, you have childhood abuse and neglect, then it becomes much harder to, to grasp this one thing that can sort of make you look good for the outside world. Well you've been around, you know, more veterans than I do. Uh, does this fit in with some of your observations? Cliff: Absolutely. A lot of times we attribute it to the leadership that you are expected to learn and to develop and execute in the military. But perhaps it is, they say folks who have been to SERE school, [00:39:00] for instance, come out of SERE school and for the rest of their lives, deal and handle stress differently than the rest of the population. Dr. van der Kolk: I think it’s probably true, yeah. You know, having parents who are real parents is very different from having parents who are getting off drunk and in the military, of course. The quality of your leadership has a tremendous impact on your mental wellbeing. Cliff: Absolutely. And morale, and just esprit de corps of the unit, all those things play a tremendous part. I mentioned this before I spent 20 years in the army, mostly in special operations. I did a ton of deployments, and I can't think of anything, any one thing that I feel was traumatic in my own experience. I wouldn't say I suffered from PTSD in any classical sense, except for, sometimes when I come back from deployment, I would have a period of hyper-vigilance where [00:40:00] I was anxious, and my wife complained that, uh, that I was irritable. But I adjusted pretty quickly. Now there's a segment of the population, the veteran population, who suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. And, you know, some of these folks never left the wire. And they can, I guess they can attribute that to this hypervigilance and having to be hypervigilant for a long period of time. What would you say to those people who quite frankly, some of them I think are often ashamed to admit that their trauma, that they have trauma when they know that others have significant trauma they didn't have to pick up a leg. They maybe just were in their bunker. And I don't know, some rockets hit the base five miles away. Now, they're still suffering from some sort of trauma that they have to get treated for, at least when they get out or even when they're still in the [00:41:00] service. What would you say to those folks? Dr. van der Kolk: Well, you know, there's something you say here that I'd like to discuss. That is, people think that trauma is about an event that happened at some point in the past, but that's not really what trauma is. An event happens that sort of changes your orientation in life, but, uh, the problem is not that event. The problem is how your brain is changed, uh, as a result of that event. So you come back from very dangerous situations and your brain is reset to become hyper alert and to be suspicious and to wonder whether people will get hurt, which makes it harder to negotiate your relationship with your wife and say, honey, it's okay. Instead of saying, “Ahh!” and becoming reactive. And so your life becomes very much influenced by your reactions that are not really part of that old memory, but [00:42:00] how you have adapted to that old situation. So you live with a different brain after having been traumatized. So the issue is how do you help live in a body that feels safe? And to my mind, a very important part of living in a body that feels safe is to pay attention to your body. That's why I did the yoga study. And what we came up with in the yoga study was that yoga was a very helpful component of the treatment of PTSD. Probably be more helpful than any medication that people take. So you need to really learn to negotiate your sensations in your body. Uh, uh, you need to, and so doing martial arts can be very helpful to help your body to become calm and to use your hypervigilance in an organized way for your martial arts moves and not on your children or your wife. So, but the event that [00:43:00] started it at some point is no longer the relevant issue what's relevant right now is how, how do I, as a psychiatrist or anybody else help you to live in the brain and feel safe right now, and that you feel enthusiastic about your life? That's it. It's really about how you live in the present. And so for example, one of my favorite treatments is neurofeedback, a brain computer interface work, where you can see how these brains are all over the place, and you can play computer games and your own brain waves and calm your own brain down. You can go to a yoga studio and calm your body down. Or you can join a church choir, and that's how you calm your body down by singing with other people. And so the big question is what can I do to help my body to feel safe and my mind to feel engaged with the present. [00:44:00] Cliff: Interesting. So I've done yoga and it's interesting, you get this feeling of euphoria. It's almost like a running high, right? But it's a very common experience that I absolutely enjoy, but I've never done it for the stated purpose of being therapeutic. We talked a little bit about morality, right? And we've discussed a little about a little of this, what I'm about to say, just a few minutes ago, but in my feeling, the way I look at it is there's few things that happen in combat that, um, that trigger traumatic feelings or stress. One of course is, you know, that we just talked about, I'm amped up all the time. Uh, and I might like that feeling. I might not like that feeling. But there's always some danger, some sense of danger. There's another one where, you know, I've seen my buddies die or be badly wounded. And then there's one that's all too common. There's this [00:45:00] feeling that I went overseas, and, for a noble cause or not, I did some horrible things to other human beings. Right? And I think that as a member of the military I've met several people who really struggle with that. It might've been an enemy soldier. You know, they talk in, On Combat , I believe the author talks about how, in the Civil War, people didn't want to kill people. They found tons of guns with a lot of bullets in them. We fixed the military in a way after World War II, by shooting at human shaped targets because they wanted to normalize that. But the distinction that somebody's trauma comes from something as, “I feel guilty for something. I feel guilty, and I don't. I can't talk about it because I might bring [00:46:00] shame to my unit or even legal trouble to my friends and comrades.” How does one... I mean, do you recommend that, regardless of the consequences, if somebody opens up to somebody about it, or...? Dr. van der Kolk: No, no. Your caution is well advised. You know, one of the earliest stories my father told me is about a neighbor kid of ours getting murdered in front of our door. I, supposed to be there as a little baby, by some Nazi soldiers. And the first time a Vietnam veteran told me about what he had done, I was freaked out by it. And I said, I'll never talk to you again. I was so upset by... He's telling me it takes a long time to be able to learn to listen to the stories. And your caution is real advice. You really need to case somebody out before you tell them [00:47:00] very, very scary things about what you have done that you feel guilty about because people may be very judgmental about it. As judgemental as you are yourself. Uh, and so you want to really make sure that the person who you confess this to is a person who, uh, who has done their own work and is able to listen to it without judgment and know that this is part of the experience that I need to help you with. And so like in our current work, um, I'm part of a team of people who explores the use of psychedelics for PTSD. And in psychedelics this issue of, uh, of moral injury, uh, is probably extraordinarily well helped because people in these states have a very deep self, uh, sense of self-compassion. And they go like, “Ah, yeah, this is horrible, [00:48:00] horrible, what I did. It's horrible, what this 18-year-old kid who I once was had to go through, and horrible that he had to do these things, and I was 18.” And they needed to come to a point of self forgiveness and you only get self-forgiveness by being with people who can accept you for just the way you are. Uh, so you can accept yourself. Yeah, this is what happened to me, but I don't have to relive it over and over again. Thank God it's over. I'll never have to do that again. So the issue of being able to somehow place it in time and to say, “Yes, this is whatever happened over there when I was 18 years old. It was different from now where I'm 40 or 50 years old and I'm living here.” That's different. A different circumstance, a different person and something in your mind needs to allow you to fully realize that which is not a cognitive issue. It's [00:49:00] not the question of, “Oh, now I understand.” It's an experiential issue of feeling what it's, the kids went through and knowing deeply where you are now. So it's a very deep, visceral experience of presence and history. Cliff: So with these treatments and this goes right into where I want us to go with, um, treatments like MDMA, maybe psilocybin, the use of cannabis. Iowaska, right. Do you believe that some of these treatments allow somebody who's suffering to confess these things to themselves? Where they don't have to tell, and I don’t have to tell you, doctor, that I did horrible things. I can reconcile within myself. Dr. van der Kolk: It really is about you and you. You and your relationship to you. And as a therapist, I'm just an intermediary for you to [00:50:00] help you to love yourself, know yourself, accept yourself, et cetera. Uh, but it doesn't come from me. I, my job is to create a situation where you can learn to know yourself and accept yourself for who you are. And, you know, it's a very complex, complicated thing, and it's hard to find, uh, you know, that's why I've spent my whole life, and I'm 78 years old. I'm still exploring new treatments because I'm not satisfied with any of the treatments we have found. The treatments I've described in my book, I've seen them work very well for many, many people, but not for everybody. And so it's always, “Okay, I'll try this. See how it works. And then after this, I'll try this, good.” Karl Marlantes wrote this beautiful book, What It Is Like To Go To War. And he writes about his whole process of, “I did that. I did that. [00:51:00] I did that. I did that. I did that.” And it oftentimes takes many different steps on this healing journey. So what bothers me about VA for example, is to say, “These people don't have a choice.” Nobody should be allowed to say that. I've got a treatment that sometimes works for some people. Cliff: Right. How close are we, do you think, to these treatments - MDMA, cannabis, iowaska - to being more mainstream for veterans or for the larger population? Dr. van der Kolk: The important thing is that there are things right now that are very helpful that I've described in my book that are not mainstream. For example, neurofeedback. Very helpful, very effective. I’ve done research on it, yoga, martial arts, EMDR. Wonderful treatments. So there are very good treatments that are available. So why the VA is never doing any of them [00:52:00] beats me because in the rest of the world, we do all the other treatments. We're not a drug-addicted group of people, you know, "Oh take it, take another pill, take another pill." Uh, so, so not everybody's excited by psychedelics for good reason. Right? What I'm sad about, is that, I wish that neurofeedback had had the same general excitement because it's available and it's legal. Cliff: Where can one go to work with...? Dr. van der Kolk: That’s the question. You have to find in your own community, somebody who knows how to do neurofeedback. Cliff: Well, maybe you'll, maybe you can send us a couple of links of some resources and we can get those to our audience. I know we're running out of time here. Dr. van der Kolk: But let me say something about psychedelics, is that they are very promising. Our data look very, very good, but you know, these are very powerful drugs and I'm worried that once it becomes legal, [00:53:00] that people will cut corners and not take it seriously and start popping pills at the wrong place and that they will not be used for therapeutic purposes. And so we'll see how it goes. Now these drugs, if used correctly can have enormous benefits, but boy, I already see the drug makers pouncing on it, "Come and get your pills. We've opened up the doors! Get your pill over here." And that's not what we do, how we do. We help people to go very deep inside. To, to, to process their own experience. That's it. We call this MDMA assisted psychotherapy. So you need to still go inside and do the work. Cliff: Right. You need to still open up the hood. Dr. van der Kolk: Yup. Need to open up the hood, exactly. Yup. Cliff: Awesome. So we're coming up short on time here, and I do want to thank you for the time you spent. I've had a tremendous conversation. To close, [00:54:00] what's the most important thing that you would tell a military veteran who might be struggling with mental health after they left the service or as they're leaving the service? Dr. van der Kolk: I would say community is critical. I don't think you can do this by yourself. Some people may be able to do it. But like, 12-step programs have done wonders for drug-addicted people. I think support groups, uh, make alliances to fuel some of the programs that I'm involved with. People have a little app ready, and can call each other at any time. It's all about community, it’s the core of health. People make people feel safe. And so it’s very important to make the linkages with other people. The second thing is that people get better. If you really devote yourself to finding out what's useful [00:55:00] for you and you have the support system that allows you to do it, explore. That's why I wrote my book, and I have all these different chapters of all these different treatments because one thing may work for you and it may not work for me. For example, for me, making music with people is a very powerful thing. For you, it may be nothing. For me, yoga is very helpful. For you, you may hate yoga. Uh, for many people, I know neurofeedback is very helpful. For other people it doesn't work. Cognitive treatments. It helps to understand how screwed up you are. But understanding why you are screwed up doesn’t make you less screwed up. Now I know why I'm screwed up, but it's not good enough. You need to have experiences that allow you to experience yourself differently. Cliff: Right. So if I'm hearing you, there's many, many techniques, but I think key among them and probably a common thread is community. You can't do it alone. Shouldn’t do it alone. [00:56:00] Dr. van der Kolk: Yep. Community. And some faith in yourself to keep exploring and to be able to register, “This was helpful.” And also to be able to say, “This wasn't helpful.” And in that, you are the ultimate authority. Only you can tell what makes you feel better and your doctor has a limited amount of information, but you know what's right for you. Cliff: Absolutely, absolutely. Well, thank you, Dr. Bessel van der Kolk. I hope to maybe talk to you again one day. We'll move this conversation even further down the road. And I want to say, I appreciate you speaking to our veteran community. I know that there's a lot going on right now with COVID and with Afghanistan and, and I appreciate you taking your time out of your day. Dr. van der Kolk: You guys have a big challenge and my heart goes out to you. Like good luck to you guys and women. Bye.[00:57:00] Cliff: All right. One podcast down; the inaugural one. Hopefully the first of many, obviously we got started with a really great guest in Dr. Bessel van der Kolk. Got pretty heavy there. It seems like it's something that is always on the front of the mind of a veteran community; we hear there's so many problems with post-traumatic stress disorder with, you know, we're losing 22 veterans a day to suicide, so it was great to talk to somebody about trauma and how to deal with trauma. Again, this is something that I think we need to hear. It's obviously something that we can take. So thank you. Thank you again to Dr. van der Kolk for joining us on the inaugural Return to Base Podcast. And by the way, if you want to learn more, you can go out and get his book, The Body Keeps the Score. It's available pretty much everywhere. Amazon. I heard it on Audible. So I listened to the tape while working out. Also, read it, got it off Amazon. So if you're really interested in learning more and hearing more, go get the book.

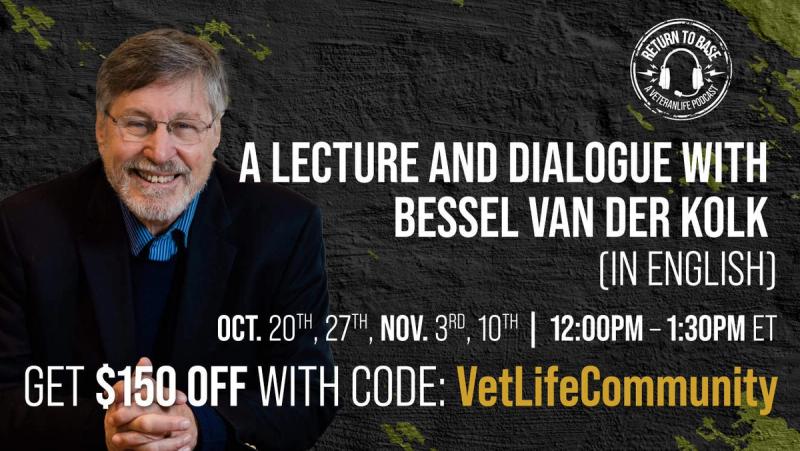

A Lecture and Dialogue with Bessel van der Kolk

Also, if you're interested in [00:58:00] learning more and hearing more from the doctor himself, he's hosting an interactive four-week program that’s meeting four times over a four week period from October 20th, and October 27th, November 3rd. And November 10th. That is, it's meeting those days, October 20th, 27th, and November 3rd and 10th from 12:00 to 1:30 p.m. eastern time. There's going to be a link in the show notes that'll take you to the registration. And if you use coupon code vetlifecommunity with no spaces. That's V E T L I F E C O M M U N I T Y no spaces. You'll get a hundred dollars. Excuse me. You'll get $150 off of registration. So you'll get that program. Grand total of $100, which is amazing. It's going to be great. It's an hour and a half of a combination of lecture and discussion with the doctor. You all heard how easy he is to talk to. He's full of information and just [00:59:00] a really great person. So go do that. So again, that's the first podcast in the books.

Conclusion

We're happy to get that over with and very excited because we have some amazing guests coming up. We have people lined up in from the business community, from the veteran service organization, community folks who are helping veterans every day. If you would please, it'd be great. If you could follow us on Instagram and Facebook and LinkedIn and all the other socials. Our handle for Instagram is @thisisveteranlife. That's T H I S I S V E T E R A N L I F E. Hope I got that right. If not, we’ll edit it out. So go to Instagram, follow us, go to veteranlife.com. That's www.veteranlife.com. You'll be able to see all the other socials, and [01:00:00] you'll also be able to see a ton of information that we're bringing in for you in the form of blogs; we'll have some tools on there. We're going to have some videos that are going to be a great place to, to come if you're a veteran or the spouse of a veteran, or just interested in reading some informative, sometimes funny sometimes maybe a little bit offensive, I don't know. If you're offended by it, we're sorry. We didn't mean to. But just good information. So thanks for joining us and we'll see you next time. Interested in more content like this? Check out more of our health and fitness articles here!

About Bessel van der Kolk

Van der Kolk got his start treating veterans while working at the Boston VA Hospital where he observed extremely troubled veterans of the Vietnam War. Having not found any academic literature to prepare one for treating these veterans, van der Kolk began proposing studies that would examine traumatic memories and PTSD. After being rejected by the Veterans Administration, who stated ““It has never been shown that PTSD is relevant to the mission of the Veterans Administration,” van der Kolk left the VA and went to work at Harvard’s Massachusetts Mental Health Center. There he encountered trauma of a different source; namely, child abuse and family violence. It was then he realized that trauma is trauma, regardless of the method of acquisition. Since then van der Kolk has researched and advocated for alternative forms of treatment that help those suffering from PTSD. Treatments like yoga, or mindfulness, and neuro-feedback.