GUADALCANAL NAVAL CAMPAIGN: IRONBOTTOM SOUND'S LEGACY

COMMENT

SHARE

Table of Contents

On the night of November 14th, 1942, some sailors aboard ships of US Navy Task Force 64 realized something was amiss with their compasses as they sailed across the narrow strip of water, then called Savo Sound, between a trio of the Solomon Islands. The magnetic needles of their navigation devices moved erratically, pointing one way and then the next. Not something a sailor, particularly one in the midst of a brutal monthslong campaign, wants to see.

But the men aboard the USS Washington, USS South Dakota, and USS Walke knew right away what caused the issue. The sound they sailed over covered the remains of so many ships sunk over the past few months, and the sheer amount of metal on the seafloor was enough to generate serious magnetic interference. Those lost ships and the dozens more that would meet their ends there before the campaign’s end the next April, which would lead to the renaming of that body of water between the islands of Savo, Florida, and Guadalcanal to one reflecting the metal-strewn naval graveyard it became: Iron Bottom Sound.

This location (sometimes written as Ironbottom Sound, Iron Bottomed Sound, or Iron Bottom Bay), the site of one of the first great sea battles in the Pacific Theater of World War II (the Naval Campaign at Guadalcanal) is an understandably hallowed place given it’s the final resting place of thousands of American, British, Australian, and Japanese sailors, soldiers, and Marines. Divers, historians, and explorers have travelled to visit the wreckage, occasionally rediscovering wrecks though lost to the murk and sand of the ocean. Perhaps the most well-known and well-regarded expedition to the sound was the one led by famed oceanographer and US Naval Reserve officer Doctor Robert Ballard in 1992, during which his team discovered the wreck of the Imperial Japanese battleship Kirishima.

And from July 2nd-23rd of 2025, that same man led another expedition to this watery battlefield. The Nautilus Exploration Program’s 2025 Expedition to Iron Bottom Sound (NA173 for short) brought back hours of stunning footage and photographs, including that of a few ships no human had previously laid eyes on since their sinking. In recognition of this amazing expedition and its discoveries, it seems like a good time to look back at the history of the US Navy’s Guadalcanal Campaign, Dr. Ballard’s first expedition to Iron Bottom sound, and share what he and his crew saw and found on their recent voyage back.

US Navy Strategy: Guadalcanal Campaign History

(Author’s Note: If you’re interested in learning more about the Naval Campaign of Guadalcanal, Neptune’s Inferno by the late, great naval historian James D. Hornfischer is a fantastic, gripping, and comprehensive read and the source of much of the historical information in this article.)

In the annals of American military history, the Guadalcanal Campaign (often referred to as the Battle of Guadalcanal) is primarily remembered as a tide-turning fight in World War II’s Pacific Theater won primarily by the United States Marines. And rightly so (ooh-rah), as Marines made up the vast majority of the landing force and carried out the bulk of the fighting on the island.

It’s the very reason why the insignia of the 1st Marine Division features the word “GUADALCANAL,” written vertically within its big, red one (again: ooh-rah). But the naval engagements that took place in the seas surrounding the island during the course of the campaign were important components of the Allied victory in this pivotal clash.

Battle of Savo Island: Guadalcanal Naval Campaign

American Marines began landing on Guadalcanal (as well as the nearby islands of Florida and Tulagi) on August 7th, 1942. The goals of the campaign were to prevent the Japanese establishing bases in the area and establish Allied ones to support the recapture of the entirety of the Solomon Islands and support the ongoing New Guinea campaign.

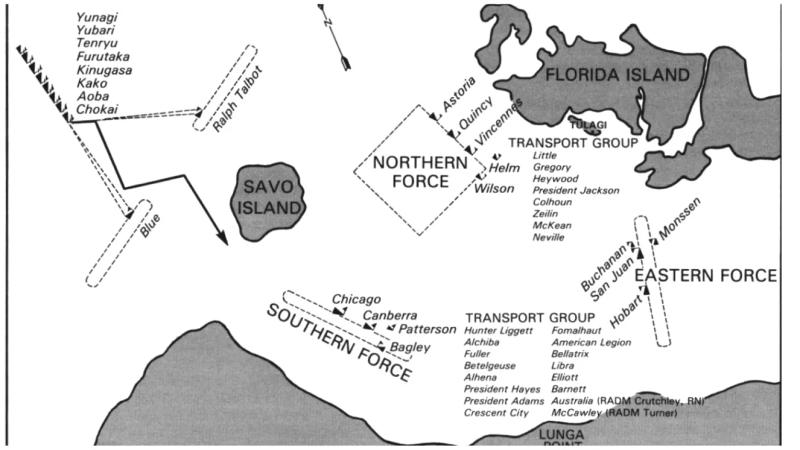

But the first naval engagement of the campaign didn’t start until the following day when Imperial Japanese forces launched a naval counterattack consisting of seven cruisers and a single destroyer. The resulting engagement ended in one of the most humiliating, definitive defeats ever suffered by the US Navy.

Following the landings, a large Allied naval force of eight heavy cruisers, fifteen destroyers, and smaller vessels from the United States, Australia, and Canada covered the transports unloading supplies and equipment on the beaches of Guadalcanal. Meanwhile, the Imperial Japanese Navy overcame their initial shock and acted swiftly, first by planning a counter-invasion.

But once the number of Allied troops involved in the landing became clear they instead assembled a strike force of seven cruisers and one destroyer at the nearby island of Rabaul. The plan was to set out in time to engage the Allied ships at night on the 8th; Japanese sailors trained extensively in night fighting prior to the war, and they hoped it might give them an edge.

On the evening of August 8, the Japanese strike force sailed down “The Slot” (the narrow channel of water between the islands northwest of Guadalcanal) and split into two groups, one to travel north of Savo Island while the other traveled south of it. Both managed to reach the seas around Guadalcanal undetected (Allied forces failed to conduct enough aerial reconnaissance and did not understand how the numerous nearby landmasses could hamper their radar, which was a fairly new innovation).

At 1:31am, the admiral in charge of the Japanese ships ordered them to attack. The southern group (which his ship, the cruiser Chōkai, was part of) began immediately. The ships in the northern group followed suit a few minutes later.

Carnage followed. In less than an hour of ship-to-ship combat in the dark dead of night, the Japanese forces used their night training and Type 93 torpedoes (dubbed “Long Lances,” they were the most advanced torpedoes in the world at the time) to devastate the Allies. The American cruisers USS Astoria, USS Quincy, and USS Vincennes were sunk, and the Australian cruiser HMAS Canberra took so much damage she had to be scuttled. Another cruiser, the USS Chicago, and two destroyers, the USS Bagley and USS Patterson, also took heavy damage. Allied losses numbered over 1,000 dead, whereas the Japanese suffered only 58 KIA and damage to three cruisers.

Luckily for the troops on the beach, the Japanese chose to withdraw their ships rather than attack the transports. Without air cover, they would be at great risk in the event of counterattacks from carrier or land based Allied aircraft. So, they withdrew and left the transports chock full of supplies that allowed the Marines to maintain their foothold Guadalcanal. Though the action was absolutely a tactical victory for the Imperial Japanese Navy, it missed a chance to potentially end the campaign in their favor.

The four freshly sunk Allied ships now lying at the sandy bottom of Savo Sound were the first of the many that would soon change the very name of that stretch of sea.

Battle of Cape Esperance: Guadalcanal Naval Campaign

The second major naval engagement of the Guadalcanal campaign was yet another nighttime duel of ships but one that saw a markedly different result. After over two months of fighting, the Japanese forces on the island needed resupply and reinforcements. They managed to make a number of quick, small resupply runs via light cruisers and destroyers, a process the Allies dubbed the “Tokyo Express.”

But on the night of October 11th, 1942, the Japanese attempted to send a major resupply convoy made up of two seaplane tenders and six destroyers to deliver fresh troops and supplies to Cape Esperance, the northernmost point of the island. At the same time, another Japanese force of five ships (three heavy cruisers and two destroyers) sailed in the same direction with the goal of destroying Henderson Field, the Allies’ vital airfield on Guadalcanal. Given their earlier success going up against the U.S. Navy and her allies at night during the Battle of Savo Island, the Japanese expected another win on the waters.

Unfortunately for them, the Allies learned from their earlier mistakes. Ships and their crews spent time practicing night fighting and learning how to better utilize and coordinate the use of radar between ships. The Japanese ships steaming to attack Henderson Field were headed towards a task group of four U.S. Navy cruisers (the USS San Francisco, USS Salt Lake City, USS Boise, and USS Helena) were far readier to face them than they imagined.

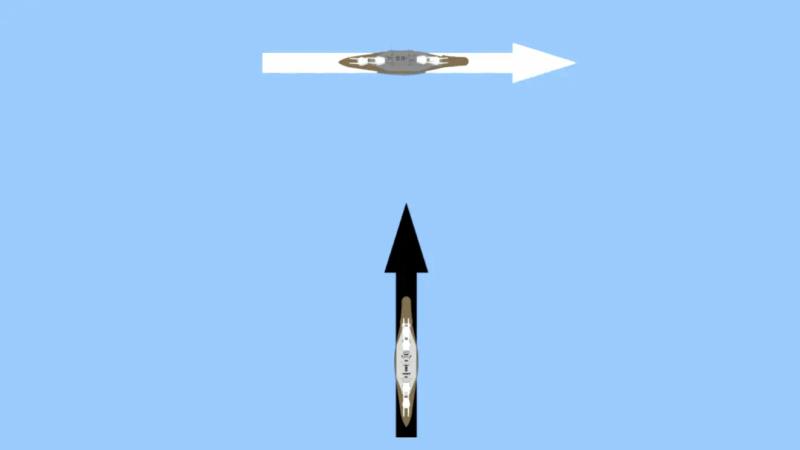

When American radar detected the approaching Japanese ships, the commander of the cruisers, Rear Admiral Norman Scott, maneuvered his cruisers into a position that would set them at a right angle to the enemy’s. Called “crossing the T” in naval warfare lingo, this would allow Scott’s ships to fire full broadsides of all their guns at the Japanese who could only return fire with forward guns.

At 11:46 pm, with rain squalls further restricting visibility in the dark of night the American cruisers opened up, surprising the unawares Japanese convoy. The first volley of shells struck the lead ship of the bombardment force, the Aoba, killing numerous sailors aboard her and fatally wounding the group’s commander, Admiral Aritomo Gotō.

The battle ended in an American victory, but a costly one that killed 163 Sailors. Friendly fire, a result of poor coordination between vessels, struck the destroyer USS Farenholt and cruiser USS Boise, severely damaging the latter. Both American and Japanese shells hit the destroyer USS Duncan, which caught fire and eventually sank. The Japanese, on the other hand, lost the heavy cruiser Furutaka, the destroyer Fubuki, and somewhere between 341 and 454 men. Additionally, another 111 of their men were captured and two more destroyers, the Natsugumo and the Murakumo, were sunk by Navy and Marine aircraft the following day as they retreated from the battle.

Despite an American success against the bombardment fleet, the Japanese reinforcements and supplies did manage to make it to Guadalcanal, strengthening their forces on the island Still, the Battle of Cape Esperance proved that the Sailors of the U.S. Navy could go toe-to-toe with their Japanese counterparts and win when properly trained and prepared.

Naval Battle of Guadalcanal: Strategic Overview

While all the naval battles described in this piece were part of the overall Guadalcanal Campaign, there’s a reason that the action fought between November 12th and 15th of 1942 is known as the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. One of the costliest naval battles not just of the campaign but the entire Pacific Theater. The outcome of this multi-phase engagement was one of the primary reasons the Japanese made the decision to withdraw their remaining forces from the island.

Determined to destroy Henderson Field and end the Allies’ ability to launch land-based aircraft against an simultaneously deployed reinforcement convoy meant to ferry several thousand fresh troops to the island, on November 12th the Japanese sent a massive task force of two battleships, a light cruiser, and 11 destroyers commanded by Admiral Hiroaki Abe towards Guadalcanal. Once spotted by reconnaissance aircraft, the Navy sent their own quickly assembled task force of thirteen ships (two heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, two anti-aircraft cruisers, and eight destroyers) under Admiral Daniel Callaghan to intercept them.

In the pitch-black hours of the early morning of the 13th (a little before 2:00am) the two forces practically stumbled into each other in the waters between Savo Island and Guadalcanal. What followed was practically a hand-to-hand brawl between ships by the standard of 20th century naval warfare, with vessels exchanging volleys within only a few thousand yards of each other.

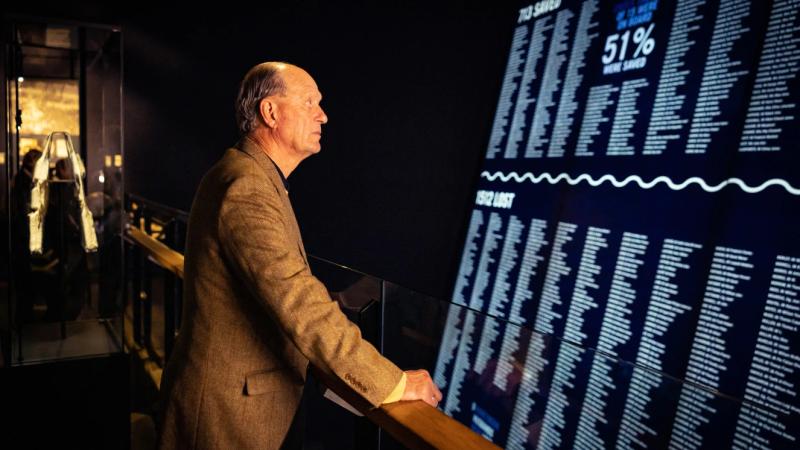

The shooting ended just before 2:30am and the two forces broke off. In the aftermath, as the two task forces sailed away from each other, aircraft and submarines continued to inflict damage and casualties on their opponents. By the time the shooting, bombing, and torpedoing let up on the 13th, both U.S. Navy anti-aircraft cruisers (USS Atlanta and USS Junea) and four of its destroyers (USS Monssen, USS Barton, USS Laffey, and USS Cushing) were sunk with two more destroyers and two heavy cruisers heavily damaged.

American losses totaled 1,439 dead, including all five of the Sullivan brothers who were serving together aboard the Juneau. Almost among the killed in action were Admiral Callaghan himself and Admiral Scott, who’d led the U.S. to victory off Cape Esperance just over a month before and was killed when friendly fire struck his ship’s bridge. Both received posthumous Medals of Honor.

The action is considered a Japanese victory, as their losses were significantly less than the Americans’. Despite the sinking of one of their battleships and two destroyers, their dead totaled somewhere between 550 and 800. But the decision of Admiral Abe, who’d been wounded in the fighting, to withdraw rather than press his attack and strike Henderson Field kept his task force from achieving its actual goal. Plus, Allied air attacks sank seven of the transport ships and forced the remaining four to temporarily halt their advance.

That night, another Japanese bombardment force, this one led by Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondō and made up of a battleship, four cruisers (two heavy and two light), and 11 destroyers, set out to attack Henderson and provide cover for the now inbound reinforcement convoy. In response, overall commander of Allied forces for the campaign Admiral William “Bull” Halsey dispatched a significantly smaller force of four destroyers and the battleships USS Washington and USS South Dakota under Rear Admiral Willis Lee.

The two forces met shortly after 11:00pm, again near Savo Island. In short order, the Japanese took all four American destroyers out of the fight, sinking the USS Preston and USS Walke and severely damaging the USS Benham and USS Gwin, the former of which had to be scuttled the very next day. Additionally, the South Dakota soon found itself unable to fight as well when a series of electrical failures knocked out radar, radios, and main and secondary gun batteries.

With only the Washington still in fighting shape, this lone battleship succeeded in crippling the Japanese battleship Kirishima (which later sank), damaging one of the cruisers, and drawing the rest of the bombardment force away from Guadalcanal. Thinking he’d successfully cleared the way for the transports, Kondō ordered his ships to break contact and leave the area just after 1:00am on the 15th. The four remaining transports of the reinforcement convoy successfully landed at Guadalcanal’s Tassafaronga Point only to come under attack from U.S. aircraft and artillery which wiped out about a third of the Japanese troops and most of their supplies.

Despite the successes of the Imperial Japanese Navy at sea, they failed to either eliminate Henderson Field or land sufficient reinforcements and supplies on the island. Thus, the battle is regarded as an overall loss for the Japanese. In the end, they lost two battleships, three destroyers and all eleven transports (even the four that made it to shore were beached, rendering them inoperable) with eight more ships damaged, and 1,900 Sailors killed (not to mention the Soldiers lost either in the landing or when their transports sank). American losses were also heavy: ten ships sunk, six more damaged, and 1,732 dead including the only two U.S. Navy admirals to lose their lives in a WWII surface engagement.

Battle of Tassafaronga: Guadalcanal Naval Campaign

The November 30th, 1942 Battle of Tassafaronga was the last consequential naval engagement of the campaign and another win for the Japanese. After their earlier unsuccessful attempts to reinforce their forces on Guadalcanal, the Japanese were desperate to land fresh troops and supplies on the island.

Their use of the Tokyo Express had allowed them to bring limited quantities of both ashore, despite the strong Allied naval presence and frequent attacks from the aircraft at Henderson Field. And at the end of November, they opted to send a force of eight destroyers along this route at once in a last try at a major resupply. Commanded by Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka, this convoy consisted of seven ships crammed with supplies stuffed into oil barrels (the plan was to dump them just offshore and let the waves take them to the beach while the ships made a quick getaway) and one full of troops.

The U.S. Navy, again acting as interceptors, sent out a force of five heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, and four destroyers under Rear Admiral Carleton Wright to head off Tanaka’s ships. After detecting them just after 11:00pm, three of the American destroyers launched torpedoes at the convoy, all of which missed. The cruisers had better luck when they opened fire with their guns a few minutes later, quickly incapacitating the destroyer Takanami, which sank a few hours later.

The Japanese responded quickly, returning fire with their Long Lances which, unlike the American torpedoes, succeeded in striking targets: all four U.S. cruisers. Two hit the USS Minneapolis, knocking out her power. One hit the USS Pensacola, crippling her. The USS Northampton took two, both near her engine room, which damaged her so severely she sank a few hours later. And another blew off the bow of the USS New Orleans, though the crew managed to not only maneuver her out of harm’s way but go on to build a jury-rigged bow out of coconut logs, sail her to Sydney for initial repairs, then sail her all the way to the Puget Sound Shipyard in Washington State (a trip they had to make stern-first) where the vessel got a new bow and underwent further repairs, eventually returning to the fight in August of 1943. The brief but bloody action ended without any further successful attacks from either side.

When the fight ended, somewhere between 395 and 417 U.S. Sailors were dead while Japanese losses totaled between 197 and 211. But while the engagement at Tassafaronga may have come off as a tactical Japanese victory that once again proved their night-fighting capabilities and the superior quality of their torpedoes, it failed to land any supplies or troops on Guadalcanal. The situation for their forces on the island remained as dire as it had before the battle.

Conclusion of Guadalcanal Naval Campaign

Despite their multiple successes in ship-to-ship combat, the Japanese forces on the island of Guadalcanal suffered loss after loss. And despite their losses on the waters, the U.S. Navy continued to prevent Japanese reinforcements and resupply from making it ashore in any significant amounts.

By the end of December, the Japanese had formally decided to withdraw all their forces from the island. And while fighting continued on land, the sea, and in the air until early February, the Guadalcanal Campaign was all but over by the start of 1943.

The last major Japanese action considered part of the naval campaign, Operation I-Go, was an aerial campaign aimed at slowing the Allied forces after their victory at Guadalcanal, failed to significantly impact their advance.

From that point on, Allied forces won victory after victory as they advanced across the Pacific towards Japan. And Savo Sound would be known to the world as Iron Bottom Sound.

Dr. Robert Ballard: Discoverer of Ironbottom Sound

Born in June of 1942 (less than two months before the Guadalcanal Campaign began) in Wichita, Kansas and raised in Southern California Robert Ballard’s interest in deep sea exploration began with the 1954 film adaptation of Jules Verne’s classic science fiction novel 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and his childhood exploration of the tidal pools around San Diego’s Mission Bay.

After graduating high school he matriculated into the University of California, Santa Barbara where he joined the US Army ROTC program. From there he went on to earn his masters at the University of Hawaii and was earning his PhD at the University of Southern California when the Army called on him to serve on active duty.

His interest in oceanography and love of the sea already piqued, he requested a transfer to the Navy. It was accepted, and he became the liaison between the Office of Naval Research and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (one of the world’s foremost oceanographic research centers). He transferred to the Naval Reserve in 1970, and eventually retired as a commander in 1995.

During those decades, he earned his reputation as a legend among oceanic explorers for his role in several historical expeditions. In the late 70’s, he took part in the submersible missions that first discovered and explored the deep ocean’s hydrothermal vents.

In the 1980s, Ballard began his search for the wreckage of the RMS Titanic which was also covered for a secret Navy mission to collect further information from the remains of the nuclear attack submarines USS Scorpion and USS Thresher, both of which sank in the 1960s. Not only did he succeed in gathering that information, but in September of 1985 he and his team discovered the wreck of the Titanic, making them the first people to lay eyes on the legendary ocean liner since her sinking on April 15th, 1912.

In 1989, he and his team discovered the wreck of the once-greatly-feared World War II German battleship Bismarck, one of the largest vessels of her kind ever built. In 1993, Ballard and his team discovered the wreck of the liner RMS Lusitania, whose sinking by the Imperial German Navy in May of 1915 was one of the main causes of America’s entry into World War I. He later went on to discover the wrecks of the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown, which sank during the 1942 Battle of Midway and of PT-109, the patrol boat John F. Kennedy commanded which was rammed and sunk during the 1943 Battle of Blackett Strait.

In 1992, Ballard and his team made their first trip to Iron Bottom Sound. During the expedition, he and his team discovered the wrecks of twelve of the warships sunk during the months of fighting there including the USS Northampton, the HMAS Canberra, and the Kirishima. The last time anyone laid eyes on those vessels, they were sinking to their final resting place at the bottom of that hallowed stretch of sea.

Ballard went on to coauthor a book documenting the expedition, The Lost Ships of Guadalcanal, which in turn became the basis for a National Geographic documentary of the same name.

2025 Naval Expedition to Ironbottom Sound

Thirty-three years after his first expedition to Iron Bottom Sound, the illustrious Dr. Ballard led another expedition to that wreck-strewn naval graveyard. Organized by the Ocean Exploration Trust (OET) and part of the Nautilus Exploration Program, the NA173 expedition lasted a full 21 days, during which Ballard and his crew made use of the cutting edge technology aboard their vessel, the E/V Nautilus, and its remote sensor platform, the Uncrewed Surface Vessel (USV) DriX, to gather data and, even more dramatically, hours of footage captured among the wrecks of the sound.

Among the wrecks NA173 explored and captured on camera were four ships that had never before had sophisticated imaging taken of them and another (the Japanese destroyer Teruzuki, sunk while trying to deliver supplies to Guadalcanal) that had not been seen since her loss in December of 1942. Additionally, they discovered the blown-off bow of the USS New Orleans, the ship that became famous for her coconut log replacement bow and backwards journey home.

We could go on and on about the incredible footage Ballard’s expedition captured of these and other wrecks off Guadalcanal, but no words could possibly do justice to the amazing images they captured in the depths of Iron Bottom Sound. So, all of you military history buffs/oceanography fans out there, do yourselves a favor and check out the expedition’s website and its many videos. They offer an absolutely captivating, unique look at the haunting aftermath of one of World War II’s most important naval campaigns.

Suggested reads:

Join the Conversation

BY PAUL MOONEY

Veteran & Military Affairs Correspondent at VeteranLife

Marine Veteran

Paul D. Mooney is an award-winning writer, filmmaker, and former Marine Corps officer (2008–2012). He brings a unique perspective to military reporting, combining firsthand service experience with expertise in storytelling and communications. With degrees from Boston University, Sarah Lawrence Coll...

Credentials

Expertise

Paul D. Mooney is an award-winning writer, filmmaker, and former Marine Corps officer (2008–2012). He brings a unique perspective to military reporting, combining firsthand service experience with expertise in storytelling and communications. With degrees from Boston University, Sarah Lawrence Coll...