BATTLE OF THE CRATER: TURNING POINT IN THE CIVIL WAR

COMMENT

SHARE

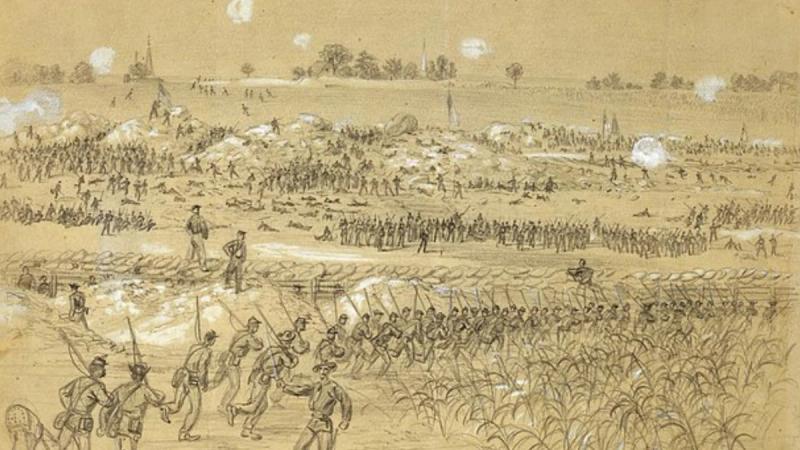

The American Civil War was characterized by both tragedy and bravery, and the Battle of the Crater serves as a powerful reminder of both. Reflecting on this tragic encounter allows us to learn a great deal about what goes down during a highly contested battle, the fallout from the mistakes that were made, and the human cost of war.

In addition to commemorating one of the major events that shaped our nation, the Battle of the Crater encourages us to remember the sacrifices made to achieve freedom and unite the country. It is always a good thing to be reminded of the bravery of those who fought and the lives lost so that we won’t be making the same mistakes again.

Battle of the Crater: Key Events and Strategies

The Battle of the Crater is considered to be the most spectacular and simultaneously the worst part of American Civil War history. From June 15 to 18, 1864, the Union launched four days of intense attacks on Petersburg's eastern defenses, starting the siege. The two troops were quickly divided by trench lines.

There were only 133 yards separating the Union lines across from the Confederate Elliott's Salient. The 48th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment's mining engineer, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants, proposed that the breakthrough could be achieved by digging a tunnel beneath the Confederate defenses and detonating thousands of pounds of gunpowder.

Despite skepticism from the commander of the Potomac Army, he approved the proposal. Lieutenant Colonel Pleasants mostly relied on the 48th Pennsylvania Regiment, which included roughly 100 coal miners who later became soldiers, to dig the tunnel.

The Tunnel Became a Key Strategy

Pleasants had virtually little logistical backup from his higher headquarters when the digging started on June 25. His men made incredible strides, searching through their shirts and underpants. Confederate Brigadier General Edward Porter Alexander, commander of artillery, had a suspicion that the federals were digging tunnels approaching Elliott's Salient before the end of June.

The tunnel was 20 to 22 feet below the Confederate forces in Elliott's Salient and 510.8 feet long on July 17. Above, the sound of the digging was hardly audible. Four days later, a story about a Union mine in Petersburg appeared in the newspaper. Pleasants stated that the tunnel was filled with 8,000 pounds of gunpowder and prepared for detonation around July 28.

In the meantime, the Union was still preparing for the onslaught following the mine explosion. Lt. General Ulysses S. Grant, the Union commander, intended to use the explosion as part of a larger plan that included protests at Richmond. The attacking force would be Major General Burnside's Ninth Corps, with Well's Hill, the location of Blandford Church, as its target.

Union artillery could cover the whole city of Petersburg from this vantage point, including its bridges across the Appomattox River and the backs of adjacent Confederate batteries to the south and west of Petersburg. They believed that if this attack was successful, Petersburg would undoubtedly fall.

Union Army's Petersburg Assault Strategy

Major General Meade vetoed Burnside's plan to assign Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero's African-American division led the attack because. Meade was afraid of being criticized if the mission didn't succeed, sacrificing Black soldiers over white soldiers. Burnside chose Brigadier General James Ledlie instead, claiming that he was incapable.

While Grant's feint at Richmond drove Confederate forces back, Burnside readied himself to enter Petersburg because he was confident in his capabilities. The mine's fuse was lit beneath the Confederate lines, and two members of the 48th Pennsylvania successfully reenacted it after a lull. A huge crater was formed, and 278 Confederate soldiers were killed when four tons of gunpowder exploded, creating a hole that was 170 feet long and 30 feet deep.

Aftermath of Union Assault: Impact on Civil War

Following the blast, 15,000 Union soldiers hurried to the crater, but they were unable to advance up Wells Hill because of the chaos. Ferrero eventually joined the Union commander, Ledlie, who continued to give instructions. General Lee of the Confederacy promptly gave General Mahone the command to launch a three-branch counteroffensive.

In the crater, these forces attacked the Union soldiers while Confederate artillery bombarded them. The Union forces were forced to retreat after nine hours of combat after Mahone's counterattack shut the opening. There were roughly 1,500 Confederate and 4,000 Union casualties in the Battle of the Crater. A brief ceasefire allowed both sides to collect the injured and dead.

Read next:

- Eight Civil War Facts That Will Blow Your Mind

- What Were the Main Causes of the Civil War?

- These Major Figures of the Civil War Shaped Modern America

Sources:

Join the Conversation

BY ALLISON KIRSCHBAUM

Veteran, Military History & Culture Writer at VeteranLife

Navy Veteran

Allison Kirschbaum is a Navy Veteran and an experienced historian. She has seven years of experience creating compelling digital content across diverse industries, including Military, Defense, History, SaaS, MarTech, FinTech, financial services, insurance, and manufacturing. She brings this expertis...

Credentials

Expertise

Allison Kirschbaum is a Navy Veteran and an experienced historian. She has seven years of experience creating compelling digital content across diverse industries, including Military, Defense, History, SaaS, MarTech, FinTech, financial services, insurance, and manufacturing. She brings this expertis...