SIGNS OF PTSD: A SPECIAL OPS VETERAN’S AWAKENING (PERSONAL STORY)

COMMENT

SHARE

Trigger Warning: this article discusses multiple forms of trauma, including suicide and mental health.

Introduction

First of all, it wasn’t supposed to happen to any of us. We were the chosen ones. We had all the traits you need to withstand the “suck factor” of being in the Special Forces: mental toughness, physical prowess, problem-solving abilities and true grit. So, when Nick—a grizzly Special Forces veteran that I went to school with—took his own life, we took notice.

But we were also quick to point to the other factors in his life that were obvious PTSD warning signs:

- Alcohol abuse.

- A rocky marriage.

- That wild personality.

In those days—the early 2010s—when we found out about suicide within the community, we looked down our noses at the departed and uttered words like, “weak” or “quitter.” You can almost appreciate the warped logic: To surrender yourself to something as simple as self-pity wasn’t keeping with the tradition of “sucking it up.” When we were active duty, if someone seemed upset about something or was going through a hard time, we’d jokingly ask that person if we could get their stereo system when they passed, or if a month was “too soon” to start dating their wife. Don’t worry bro, I’ll treat your kids like my own. Hard treatment for hard men.

Keeping Feelings Bottled Up

Shockingly, and without scientific data to back it up, the callousness of the team room didn’t help. Certainly, we meant no harm, but we—the leaders and future leaders of the Special Operations Forces—were bolstering an environment where it was dangerous to be “open” and “vulnerable”. The result? Rather than getting the help we needed, we kept our emotions and thoughts bottled up. Speaking of bottled up, we drowned our feelings with alcohol and other unhealthy pursuits. We tried at all costs to maintain an aura of stoicism. That’s what kept us sharp on the battlefield; certainly, we could apply for the same medicine at home. Wrong. The bodies began to pile up, and I don’t mean on some distant dusty battlefield. Between 2007–2015, 117 of our elite Special Operations Forces died by their own hand. To put this in context, that’s more than 33 for every 100,000 of us...and the conventional forces, not special operations, weren’t far off either, with almost 23 per 100,000 over the same period. In a private Facebook group for Special Forces members only, posts with links to articles with headlines like “Special Forces Soldier found dead in Fayetteville, Investigation Ongoing” became more frequent. The comment sections revealed much more, although never explicit. “Rest in Peace, Brother!”, “Hope you’re at peace. De Oppresso Liber.” Message received. Another brother gone too soon. Another victim of our criminal apathy. In the final years of my own military career in Special Forces (one that spanned 20 years and many deployments), the negative attitudes toward mental health, PTSD and suicide softened a bit. It could have been a consequence of the myriad briefings we would have to attend each year—before deployment, after deployment, annually as a battalion, again if you attended a professional development school—or, the victims of suicide started to hit closer to home. What started out as “Yeah, I maybe sort of knew that guy” became:

- “Not only did I know the guy, but I knew his family...”

- “I was on the same deployment and in the same firefights...”

- “This guy looked a lot like me...”

- “God, that could have been me!”

Unfortunately, this newfound empathy didn’t have a remarkable effect. In 2016, there were 17 cases; in 2017 there were 8; then, in 2018—my last year in the service—there were 22. At some point during those last three years, I began to feel overwhelmed by the rigors of planning and preparing for my life as a civilian. Worse, I began to sink into depression as I realized my life as an Action Guy was coming to an end.

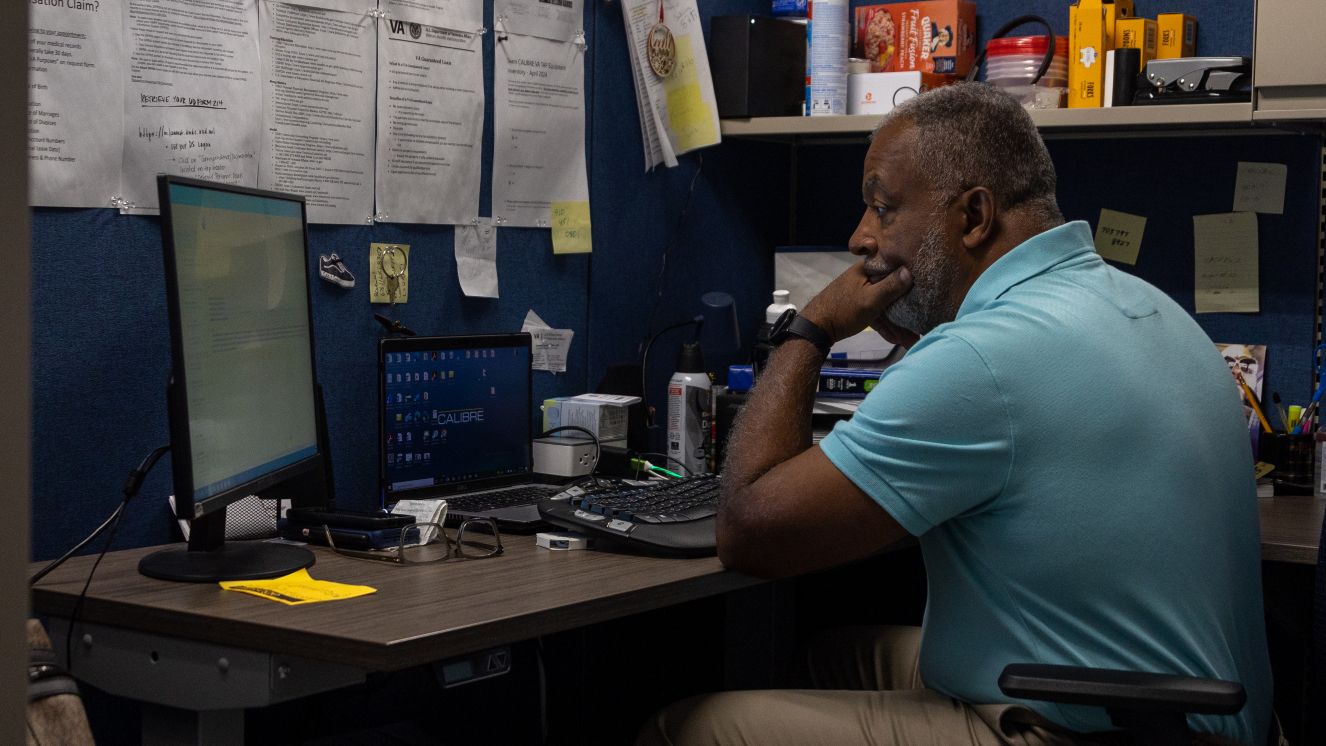

Coping with Transitioning Out of the Military

While working a thankless staff job, going to graduate school, being a husband and a parent, attending transition briefings, etc., I realized I’d already had the best job I’d ever hope to have. Before, I was a leader in the Special Forces. Now, I’m just another face in the crowd. It reminded me of that scene at the end of Goodfellas where Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) says, “I'm an average nobody. I get to live the rest of my life like a schnook." I didn’t feel suicidal, but I knew I needed help before the feelings of depression spun out of control. Feeling very “schnook-like,” I made my case with the Battalion doc during a periodic health reassessment. His response? “Make an appointment for sick-call.” You’ve got to be kidding me right? I did not make an appointment for a sick-call. I felt humiliated and defeated...and worse, I understood the fight against suicide was far from over. I bit my lip and did my best to keep cool for the remainder of my military career. Finally, at my retirement appointment, I complained about having the early warning signs of depression and PTSD and received treatment. Luckily for me, it wasn’t too late. Looking back, I may have dodged a bullet. But I was wrong to think that my part of this story was over. With so many of my close friends still on active duty, it seemed like only a matter of time before I would be called into crisis. Newsflash, the pain doesn’t stop when you get your DD214. My circle of friends, and family, included a large number of recently transitioned veterans as well.

Experiencing PTSD Symptoms

Called to action. Nothing prepares you for when your buddy’s wife calls and asks you to come quick. “He’s in a real dark place. He’s been drinking all day, He’s talking about suicide. Come quick!” Chris is a 220-pound wall of muscle, has tattoos, Harley Davidsons, a lot of guns in his house, and a taste for white lightning (moonshine). When I arrived at his house, he was beyond drunk and sobbing uncontrollably. Being a very close friend, my first question was “What the f*** is happening?” Although I was trained to recognize the signs of PTSD, I wasn’t ready for this. Until now, I had no idea that he was suffering from debilitating PTSD—although you’d think with somebody close enough for my kids to call “uncle,” I might have noticed. Slowly, through slurred speech, he revealed the demons that had been haunting him every day for the last decade. Over and over again, he told me that he didn’t deserve to be alive and couldn’t bear to be in the presence of innocence—his infant daughter—when he felt so deeply guilty about the things he had done on the battlefield. For my part, I listened, and I even took him fishing in a nearby pond, which seemed to make him feel better. Then, I did what so many others have done: I chalked it up to alcohol, combined with the stress of transitioning out of the military. I took him back to his house, made sure he was sleeping and went home. Thankfully, he slept it off and the crisis was averted. Called into action, part two. I didn’t expect for his demons to go away, but I did expect Chris to seek some sort of treatment. He didn’t. Within a few weeks after the first episode with Chris, I received a call from Jeff, our former teammate that lived two states away. Long story short, Jeff said Chris was in the exact same condition as before: drunk and sobbing. Jeff was driving as fast as he could to Chris’ aide. Jeff's question to me: “What the f*** is happening?” Well, at least I wasn’t the only friend oblivious of Chris's struggles. We had another long night of consoling, listening, and “being there.” This time, however, I realized I made a near-fatal error during the previous episode and vowed not to do it again. This time, I wasn’t leaving until we had a plan in motion. Getting the command involved is no small matter. Luckily for me, I still had the same phone as when I was active duty and was able to communicate the situation to the right people. Still, even as a former soldier at this point, I felt almost guilty about reporting Chris’s situation to his chain of command. Nobody—and I mean nobody—wants the Sergeant Major and the Commander in their business. But if we were to get real help, we needed it to come from the unit, and I needed to spirit a sense of urgency. “NO, 72 hours from now will be too late! We need a bed in a treatment facility RIGHT NOW. “ Chris went away for a month. They took his shoelaces and made him attend group sessions where he met other service members and veterans dealing with similar issues. The doctors took a hard look at his medications prescribed over the years and applied like band aids—never meant to be left on as long as they were. Small changes made a big difference in his mood, and a month of clean living brought a color to his face that had been missing for so long. I’d like to say he was out of the woods, but that would be a mistake. In reality, no amount of therapy or meds would ever erase the memories, let alone the trauma. No, he is in a better place, but still in the woods nonetheless. So what now? Armed with the experience, one feels compelled to share. It’s not just the tough exterior and pride of he who suffers that needs to be shed. We—the support, the shoulder, the family, the battle buddies—must also shed our exteriors and put our pride aside. We must be able to listen more than we hear, see what is right in front of us, and act boldly where we might have let it play out.

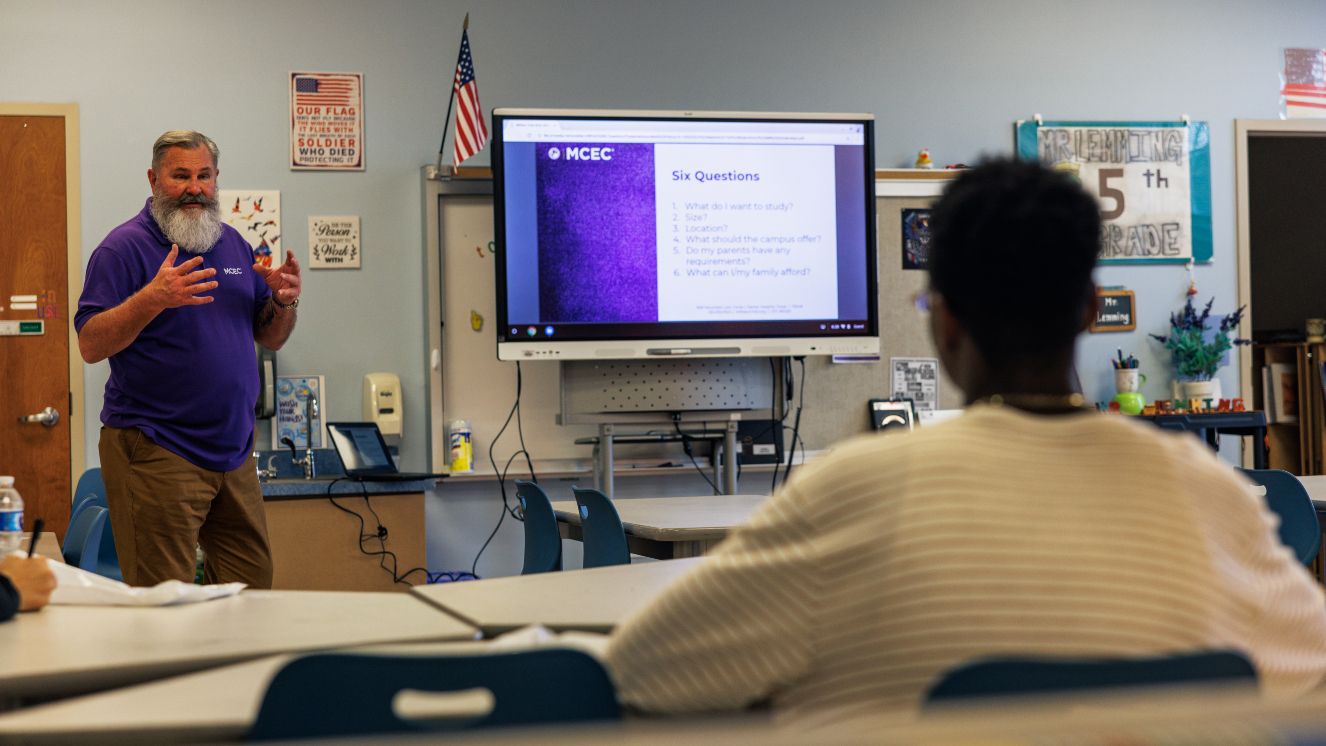

Get Educated: PTSD Resources and Tips

If you or somebody you know is experiencing signs of PTSD, do something. There’s a ridiculous amount of PTSD resources out there. As with most things for vets, start with the VA. Here are some other simple yet effective ways to do something.

1. Listen and be Empathic

Encourage your buddy to let it all out. In large part, the pressures to keep it all in are what brought us to this state to begin with, the fear of being judged, mocked, or ridiculed. Let your buddy know you are there to listen and that you feel their pain.

2. Encourage

Opening up isn’t easy. Indeed, it takes courage to let yourself be open and vulnerable. Let your buddy know that he’s doing the right thing by talking to you.

3. Phone a Friend

Although this doesn't apply to every situation, it’s very possible that your buddy isn’t the only one in your circle that has been through this situation. If you know of a mutual friend or trusted colleague, ask them to Facetime or Zoom or Skype or even come on over. Being the sole support can be exhausting; it helps to have a second.

4. Call for Help

You might need to enlist outside, confidential help. The Veterans Crisis Line offers free, confidential support, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year: Call 1-800-273-8255 and Press 1 or Text 838255.

5. If your Buddy is Still on Active Duty

Seek help from the unit; the Commander has a vested interest in the health and wellbeing of his soldiers. Although not perfect, the military has been lining up resources to address these issues and is often under-utilized. Demand help!

Conclusion

Again, this can be an exhausting ordeal for everyone involved. If you feel you need to talk to someone, call the hotline or phone a friend or family member. It will do you no good to keep your own feelings bottled up. Do you have any advice or recommendations for a veteran struggling with PTSD? Please feel free to share them in the comments section.*The statements on this blog are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease. The author does not in any way guarantee or warrant the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any message and will not be held responsible for the content of any message. Always consult your personal physician for specific medical advice.